The establishment of power under democratic parameters in a fair number of countries is a well-known fact, after what became to be known as the third wave of democratization that took place in the last quarter of the last century. Democracy was configured as a form of exercising power in which elections played a crucial role, accompanied, however, by other institutional aspects related to the rule of law, the values of coexistence and a certain level of socioeconomic equality. Consequently, the relationship between elections and democracy is univocal. Democracy doesn’t exist if elections aren’t held, but elections alone don’t bring democracy.

In political theory, this scenario has been seen in the last decade by analysts at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, working under the umbrella of the Varieties of Democracy research project. Their vision is relatively simple. They conceive democracy as a polyhedron of five faces, each of which is differentiated from the rest of the set and functioning as varieties of democracy: electoral, deliberative, egalitarian, liberal and participatory. Each of these is then broken down into different components that are measured with simple scales, which are tied to researchers’ observance level, generating an index that makes it possible to analyze their evolution over time and compare them from one country to another.

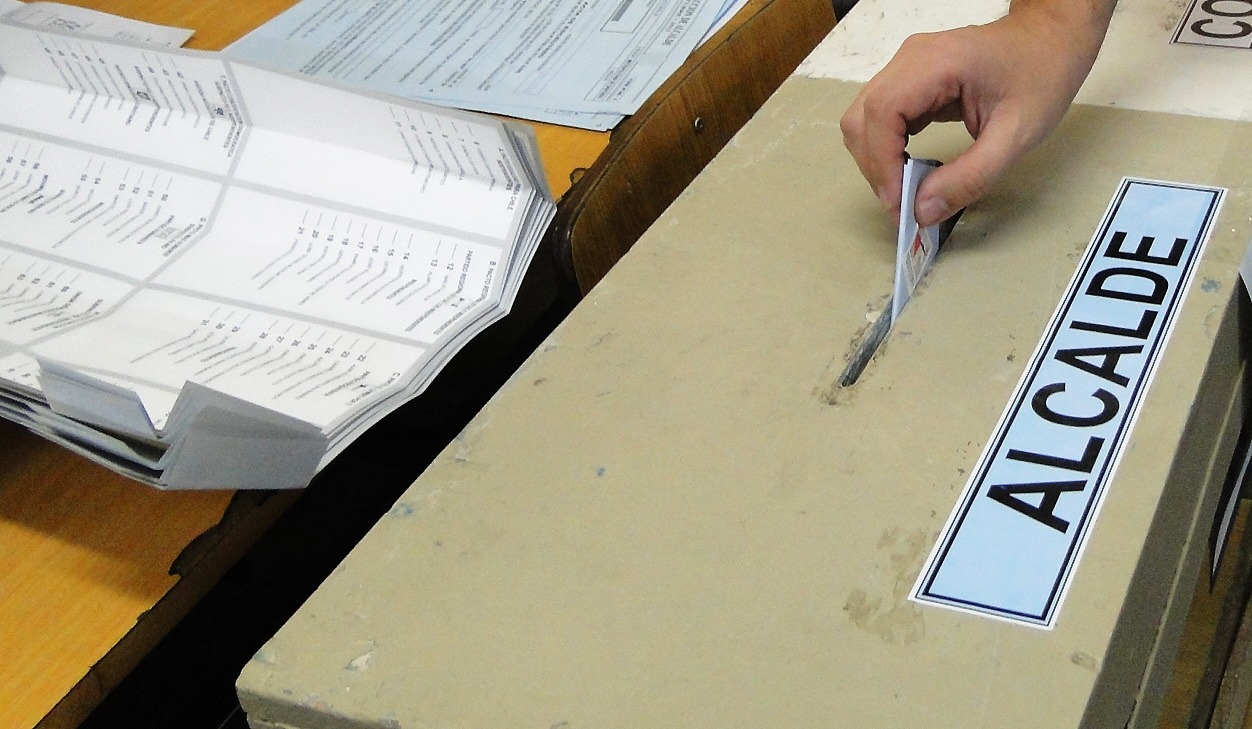

With very few exceptions, Latin American politics has revolved fundamentally around the electoral dimension of democracy in the last three decades. This variety emphasizes the freedom of speech and of association, clean elections, the extension of suffrage and the existence of elected public officers. The electoral issue has been reasonably well satisfied in Latin America with elections held periodically and with results recognized by the parties, producing the victory of the opposition in practically half of the cases.

The data of the previously mentioned research project in Sweden validate this circumstance by placing the indices of electoral democracy over time above the other four. This is largely due to a fortunate combination, in general terms, of institutions that have functioned correctly and a citizenry, whose behavior has followed patterns of undoubted maturity.

However, in the complex arena of power relations, tensions that reveal clear confrontational positions still exist. Last week, what happened in this regard in Brazil and Mexico is evidence of it and, simultaneously, proves the deterioration of the five aforementioned varieties. In Brazil, as of 2016 and in Mexico, after 2018. In both cases, political struggles between the State’s powers call into question the electoral processes and even the arbitration body.

In Brazil, on April 15, the Supreme Court decided, with eight votes against three, to uphold the ruling that had previously annulled the corruption charges against former president Lula in the Lava Jato case. The Court ratified that he shouldn’t have been tried in Curitiba—in the court then occupied by Judge Moro, later Justice Minister under Jair Bolsonaro—so the sentences imposed there were annulled and the files will be tried in Brasília.

This does not mean that former president Lula has been acquitted, since the decision is that he will be retried for three other corruption cases—in which he is accused of receiving perks from companies in exchange for public contracts. But he is fully qualified for the 2022 electoral contest, which is a drastic change in the competition’s expectations.

In Mexico, the president of the Supreme Court, Arturo Zaldívar, has seen how the Senate has extended his mandate for two years. This decision was denounced by the opposition as unconstitutional, which has once again evidenced the interference of the ruling party in the judicial branch. The Mexican constitution establishes that the maximum term for the president of the Court is four years, without the possibility of immediate subsequent reelection.

The Federal Judiciary Council, which is judges’ governing body, has insisted that it has neither drafted nor requested the measure. Zaldívar has been an extraordinarily important figure in the complex issue of the energy reform that is one of President López Obrador’s star projects. Mexico’s president, who still enjoys a 63% approval rating, a Reforma newspaper poll showed on April 16, sent a letter to Zaldívar in March, formally requesting an investigation of the judge who temporarily suspended the application of the new law.

This adds to the serious tension generated by the ruling group regarding the actions taken by the National Electoral Institute (INE) to exclude two gubernatorial candidates from the contest, and order the president to withdraw the morning conference for not complying with the electoral ban. The rigorous work of INE’s president, Lorenzo Cordova, is now being questioned and puts the entire electoral process at risk by promoting the discrediting of the mechanisms that regulate it, as well as of the officials themselves.

The dimensions of power under democracy’s umbrella constitute a framework of unstable equilibrium. The disregard for the rules of the game and for those instances that imply control and balance around the State’s powers, further jeopardizes the future of tired democracies, articulated in a scenario where the malaise of the citizenry and the crisis of political representation stand out.

Translation from Spanish to English by Ricardo Aceves

Photo by Red Mi VOZ