Latin American politics comprises an increasingly varied number of electoral processes. They range from primaries to referendums, legislative elections, and also to elect the highest judicial bodies. However, the presidential election remains the apex moment for citizens, parties, and media, as well as for the international community’s interests.

Three presidential elections are scheduled for 2023: in Paraguay (April), Guatemala (June), and Argentina (October). In addition to these elections, which are scheduled in the corresponding constitutional calendars, the presidential elections in three Andean countries could be brought forward. Indeed, with varying degrees of probability, Peru could go to the polls, as an attempt to overcome the precarious governability; Ecuador, if cases such as the impeachment of the president and the dissolution of Congress move forward; Venezuela, as a new episode in the tug-of-war between the regime and the opposition. The mere consideration of these cases ratifies the turbulence that regional politics is going through.

Regardless of whether there are three or more, the presidential elections will be held in the “pandemic cycle” opened in 2020 and marked by the confluence of sociopolitical, economic, and health crises because of COVID-19, which have accentuated citizen unease with respect to institutions and authorities.

In the electoral field, this phase is characterized by diminished participation; the difficulties of the ruling party to retain power, and the good wind for the opposition, whether traditional or embodied by an outsider. In addition, these elections have been distinguished by the rise of defensive rhetoric of traditional-type moral values and the growth of social networks as a political and campaign arena. Most likely, the continuity of these trends will combine in different ways and there may be exceptions in each country.

The most definite case is Paraguay, one of the last remaining historical bipartisanship in Latin America. In what is expected to be a tight race, as was the case five years ago. Santiago Peña, of the ruling Colorado Party, winner of six of the seven elections since the return to democracy, and Efraín Alegre, leader of the Concertación, a coalition that brings together right-wing and left-wing organizations and is organized around the Liberal Party, will face each other. Their confrontation had been foreseen for almost a year and was ratified after the respective primaries. The margin of surprise of third candidacies seems reduced. At stake is the permanence of the Colorado Party in the Government or its second exit from power in more than three decades.

In an unfavorable wave for the ruling parties, the Colorado Party has assets to play, including a structure with a great capacity for territorial mobilization, resources, and loyalty to the colors of the organization. Peña is confident that his membership in the opposite wing of the party will allow him to retain those dissatisfied through the promise of alternation within the same spectrum. For his part, Alegre seeks to channel dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy and the state, aggravated by the perception of widespread corruption. Thus aspires to do so through the promise of an alternation. However, the campaign focused less on the public policy debate than on the U.S. sanctions against the former president and leader of the Colorado Party, Horacio Cartes, as well as against other leaders of that party for “significant corruption”.

In Guatemala there are fewer certainties. In one of the most volatile and fragmented political systems in the world, no party has managed to get re-elected or return to power: each and every ruling party has been different. The deterioration of democracy, with restrictions on freedom of expression and reduction of judicial independence, forms the backdrop. The ruling party’s chances seem slim.

For now, two women with political trajectories stand out in the polls. Zury Ríos, daughter of a military president, and former first lady Sandra Torres, the latter more progressive. Both and other aspirants must still complete the validation of their candidacy, a stage that has proven not to be a mere formality, as illustrated by the disqualification of Thelma Cabrera, a critical voice against the status quo and close to the indigenous movements. The hurdle to her nomination has tarnished the credentials of the elections. As has invariably occurred since the establishment of democracy, everything points to a second-round resolution.

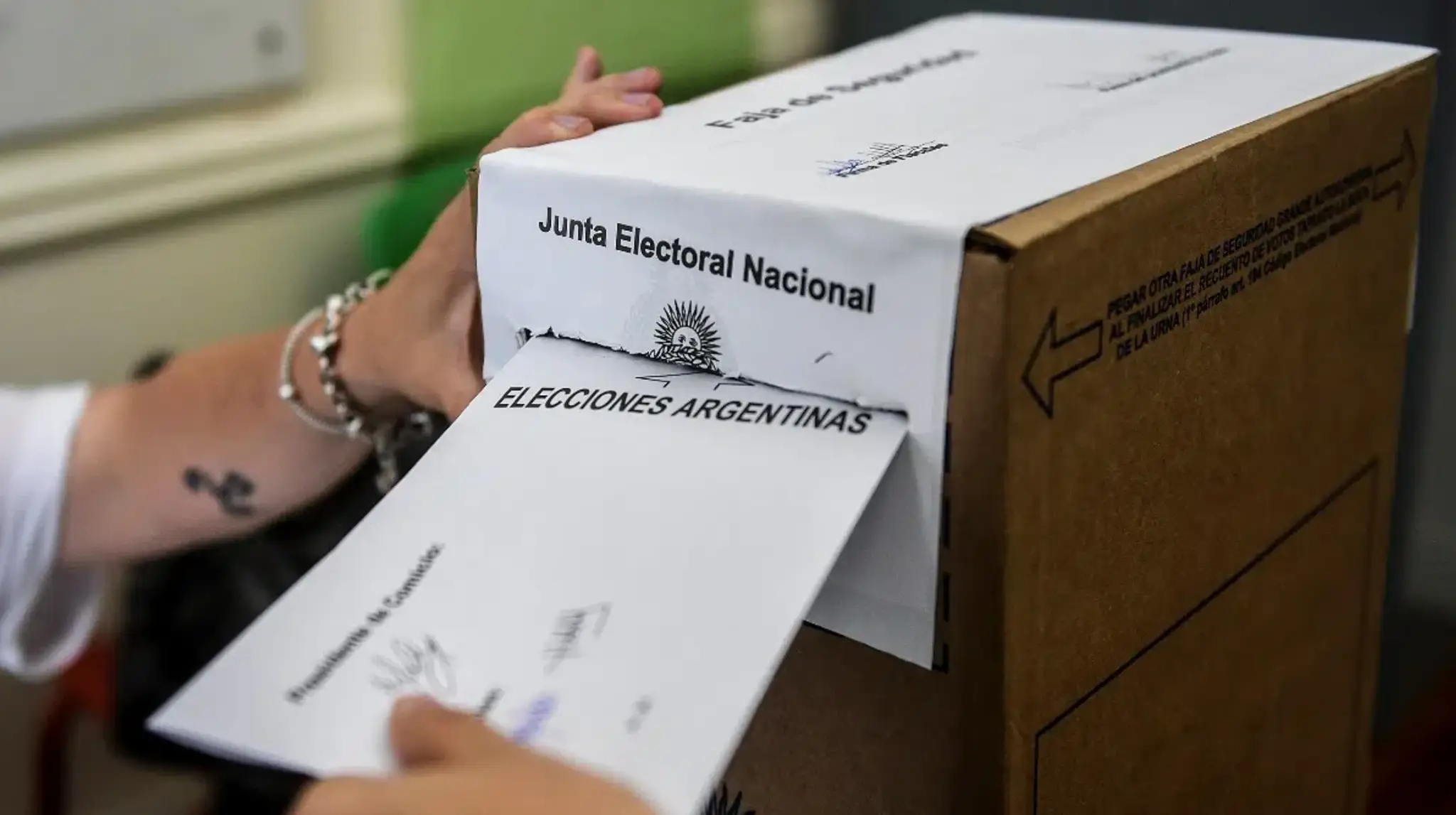

Of the three elections, Argentina has the most significant electoral roll. Despite being one of the leading economies in the region, it is dragging strong and endemic inflation and devaluation, which hinders growth, generates frustration, and forces continuous and conflicting negotiations with international organizations and workers’ sectors.

Numerous unknowns remain in the electoral equation. If Paraguay and Guatemala prohibit reelection, Argentina authorizes it, but Alberto Fernandez’s options, should he decide to run, seem modest. This does not mean that the ruling party is out of the fight, since the motley galaxy of Peronism can promote a candidacy that vindicates the government balance (if good developments take place, which are increasingly improbable), as well as another one that emphasizes criticism (in the opposite situation).

The liberal opposition will have to reconcile its own disputes, the tone of which is hardening, while that which emerges at the borders of the political system, with a frontal message, is waiting to reap the fruits of weariness. There is still suspense as to who will be on the ballot. Little by little, the candidates that will have to pass through the sieve of a primary with a taste of an early presidential election due to its simulation nature for the parties and mandatory for citizenship are being unveiled.

Latin American politics will continue to be reconfigured by the results of these presidential elections, but will remain under the tense sign of the uncertainty of incoming governments to which societies give short-term credits and strong conditions.

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva