In its offensive against the terrorist group Hamas, which on October 7, 2023, invaded southern Israel killing more than 1,000 people and kidnapping 150, the Israeli army, under the command of Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, has had no qualms about killing thousands of civilians in the Gaza Strip: as of January 17, the dead were estimated at almost 25,000 and the wounded at more than 60,000. Schools, hospitals, mosques, and markets have been the target of multiple bombardments under the justification that terrorist cells are hiding there, without considering the innocent. The offensive is not only military. Israel has blocked communications and the Internet and has interrupted the supply of food and medicine, in addition to cutting off electricity and drinking water, which has generated a humanitarian crisis in that region, where a little more than 2,300,000 people live. Calls by the UN to allow access to essential supplies have fallen on deaf ears.

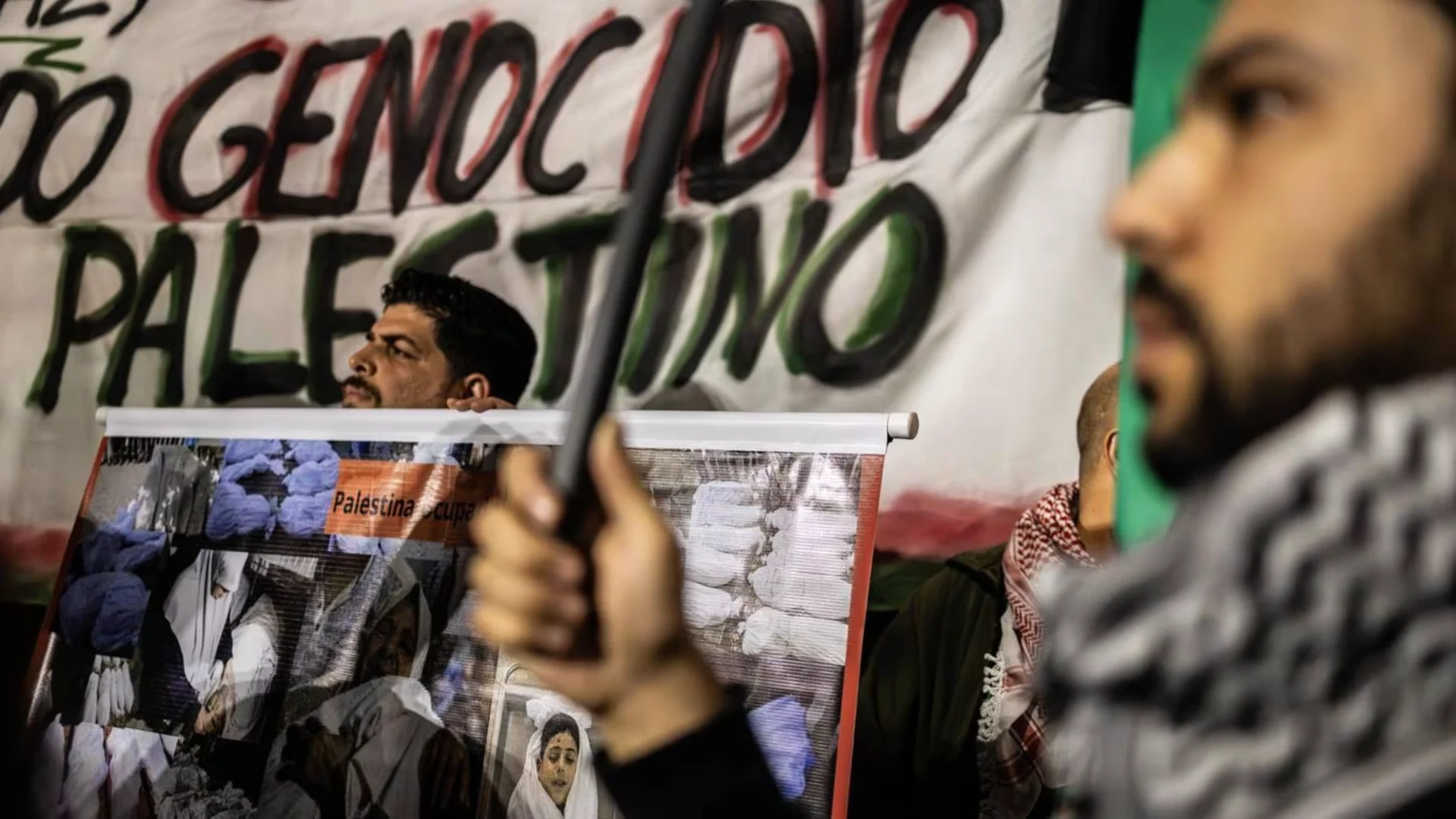

Although most Latin American governments condemned the Hamas attacks, once the consequences of the Israeli offensive — which involves serious violations of international humanitarian law — became known, Brazil called it genocide, Bolivia cut relations with the country and the governments of Colombia, Chile, and Honduras recalled their ambassadors for consultations. But the rest of the Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Paraguay, and Peru, have preferred to remain silent, while Mexico justified that Israel “had the right to legitimate self-defense”.

In the face of this offensive, preceded by declarations of Israeli politicians such as “wiping Gaza off the face of the Earth”, the South African government has taken the cause of the Palestinian people to the United Nations International Court of Justice (ICJ). Pretoria argues that Israel violates Article 2 of the 1948 Genocide Convention. The United States, Britain, and Germany have rejected this request, while the rest of Europe has remained silent. Most of the governments supporting this petition are from the Arab world and Africa. Of those from Latin America, only the governments of Brazil, with Luis Ignacio Lula Da Silva, and Colombia, with Gustavo Petro, have decided to support South Africa’s demand.

The “just war” theory

When can war be justified? Wars are a central part of human history. For centuries, they were characterized by war strategies involving the mobilization of thousands of people and weapons to fight hand-to-hand. But since the 19th century, new technologies have taken warfare to inhuman levels. Today’s new weapons can dispense with the need to look the enemy in the face, which in practice is reduced to merely identifying the target on a screen and pressing a button. The extreme is the atomic bomb, the use of which would entail not only defeating an enemy but the likelihood of destroying the whole of humanity.

In 1977, Michael Walzer outlined a framework for understanding war in contemporary societies. The first is the ius ad bellum, which are the requirements that justify a state resorting to war: just cause, right intention, public declaration of war by a legitimate authority, last resort, and proportionality to the means used. The second, ius in bello, deals with the injustices that may arise once a war is initiated, and articulates conditions to be considered: avoidance of civilians and innocents, proportionality in combat, attack on legitimate targets, and prohibition of weapons and methods that are unacceptable to the moral conscience of mankind. And ius post bellum, i.e., the fairness or unfairness of agreements leading to the end of hostilities.

Many would argue that Israel’s case against Hamas escapes these conventions because the war against terrorism is different from wars between states. Terrorists, even if they have a political code, are almost always treated as mere criminals and not as soldiers in a war. But no one doubts that the actions of the Israeli state meet almost all the elements of jus ad bellum to be considered a “just war”. If this is so, wouldn’t you expect that the requirements for avoiding injustice during war are also met? There are thousands of innocent dead, there is no proportionality, the legitimacy of many targets is dubious, and the killings and inhumane measures that are affecting civil society are unacceptable.

Committing to peace

Taking a rational stance on this case in an age of political correctness ad nauseam has led to absurd situations. Such as the cancellation of the Hannah Arendt Award to Jewish writer Masha Gessen for criticizing Germany’s staunch defense of the Israeli government and for comparing the siege in the Gaza Strip to a Jewish ghetto. Many influential international newspapers have preferred to be condescending to Israel when writing and reporting on the situation. But since words are the lenses through which we see the world, so to transfigure the facts just to spare sensitivities is also to deny their gravity.

Accustomed to seeing terrorists as criminals, attention is diverted from the origin of their political motivations, and this nature is even denied, but it is there. There is no possible political response or solution when the parties seek the destruction of one over the other. However, as Arendt pointed out in 1950 when referring to the Jewish-Palestinian conflict, “no moral code can justify the persecution of one people in an attempt to redress the persecution of another”.

With some exceptions, most Latin American governments prefer to remain silent in the face of atrocities that may be committed in other latitudes, such as the wars taking place in Ukraine, the Middle East, and Africa, either because they hide behind the 19th-century logic of the “self-determination of peoples” or for fear of being evaluated with the same yardstick and ending up in international tribunals. Establishing a clear position in the face of conflicts should be a sign of your commitment to peace in the world. Therefore, condemning the killings of innocent Palestinians by the Israeli army does not mean validating Hamas’ terrorist attacks against Israeli society, but failing to do so by trying to appear neutral is a way of condoning both atrocities and several Latin American governments are adopting this regrettable position.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish.