At the beginning of La Odisea de los Giles (Heroic Losers) — the stupendous film directed by Sebastián Borensztein (2019) and inspired by the book La Noche de la Usina (2016) by Eduardo Sacheri — the main character of the story, Fermín Perlassi (played by the incomparable Ricardo Darín), presents what will be the plot of this excellent feature film. Looking up in the dictionary the meaning of the word “gil” — a very derogatory term in Argentine slang—, Perlassi relates that, “according to the dictionary, ‘gil’ ‘is a slow person, who lacks liveliness and mischief’ (…), although we already know that [terms such as] worker, honest guy, people who obey the rules, end up being synonyms for gil (…). But one day, the abuse to which we ‘giles’ are accustomed becomes a real kick in the teeth, and you say enough!”

The opposition between the honest (the “giles”) and the dishonest (the “artful”) that the film suggests is not new (as a long-standing feature of Argentine political psychology) and has many antecedents in the studies of political science, sociology, and history, among which the well-known work of Carlos Nino, Un país al margen de la ley, stands out. Thus, the film tells us that, outraged by the 2001 corralito crisis, a group of friends from a small rural town in Buenos Aires decide to undertake a very risky and uncertain adventure to recover the kidnapping of their savings in dollars, in which, in addition, bank officials from the same town are involved. Although the feature film was released in 2019 and discusses the already then distant corralito, one cannot avoid thinking of it as an almost anticipatory metaphor of what would happen with the recent result of the second ballot in Argentina: despite the fears and uncertainty generated by the candidate who would be the winner, anger (bronca in Argentine code) would mobilize millions of voters to vote against the ruling party political proposal. The campaign that Massa represented an artful and subtle deceiver — consecrated with the adjective of “advantage” with which Mauricio Macri would baptize him — seems to have had as a reverberation the invocation of the idea, very sensitive and painful for certain sectors, that being honest, hard-working, or obey the rules is for “giles”, is for fools. These voters, fed up with this vision (which many still advocate), would have decided to vote against the “artful” of the second ballot, the “opportunist” Massa.

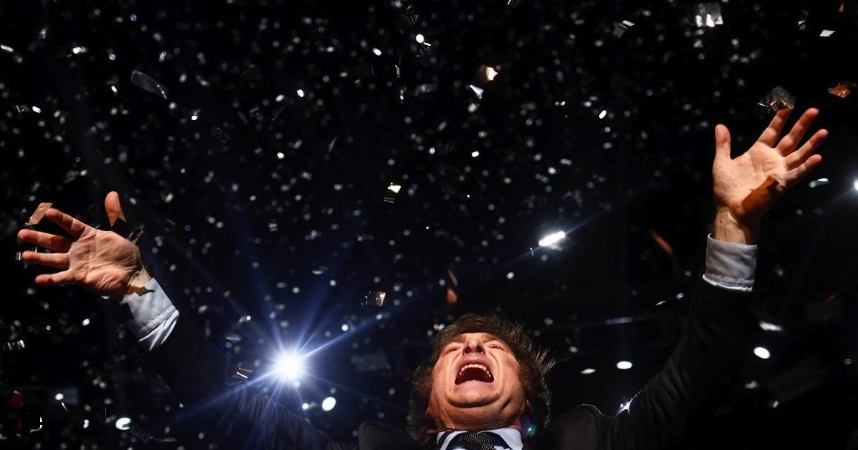

As a corollary to the idea that anger seems to have been the emotion that catalyzed a good part of the vote in the second round (an emotion that many polls and focus groups registered in the run-up to the election), the question about the governability of Javier Milei’s presidency emerges. The forty years of Argentina’s relatively young democracy testify that, except for Macri’s government, no non-Peronist party or coalition was able to finish its mandate. The growing polarization — both ideological and affective — sharpened in the last stretch of the electoral campaign with strongly negative messages from each of the two political forces does not seem to augur the formation of a sufficiently broad and consensual government base. Polarization is observed not only among the parties but also among the citizens. The calls for resistance in the streets by different economic and social actors on the very next day of the second round anticipate a very complex panorama in terms of governability. Just as a couple of examples among other expressions — listed as “coupist” by sectors related to Milei —, the director of Argentina’s Airlines Union, Pablo Viró, stated that “if they want to take over Airlines, they will have to kill us”. A day later, the priest Francisco “Paco” Oliveira stated: “I do not believe that this government will last four years” and that “if you voted for Milei, do not come here to search for food”, alluding to the dining room for indigent people that he runs in Merlo.

It is important to consider the economic and social starting point of the Argentine government that will take office on December 10. The incoming president will receive a country with negative reserves in the Central Bank, an inflation rate of 140% with an estimated projection of 300%, a significant distortion of relative prices, fourteen exchange rates against the dollar, poverty levels of 40%, and indigence of 15%, a very high public debt not only with the International Monetary Fund but also with the so-called “swap” with China and with other public and private entities. Due to the scarcity of dollars, Argentina has had difficulties importing from primary products to fundamental medicines, critical hospital supplies, and key supplies for the automotive industry.

The enormous effort made by the ruling party to reach the elections in an electorally competitive condition (despite the severe difficulties resulting from Massa’s management as the Minister of Economy) was done by appealing to economic policies characterized by hard problems of temporal inconsistency: the present was exclusively privileged to make its consequences fall back on the future. The aim was to get to the elections as well as possible and then see. In the eighteen months of Sergio Massa’s ministry, issuance increased the monetary base by 100%. Policies aimed at improving the electoral chances of the official candidate cost between 1.5 and 2.5 points of Argentina’s GDP. Tax cuts to the most privileged sectors in terms of income, or the so-called “platita plans” — such as distributing perks impossible to sustain in time and which ended (precisely) with the holding of the elections — seem to have put this country in front of what Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Prize in Economics, called the tragedy of the commons: if a village cuts down the whole forest today, there will come a time when there will be no more trees to cut down.

The room for maneuvering for the incoming government is tiny. It does not seem an exaggeration to state that, from the results of the so-called “path dependence”, the almost twenty years of Kirchnerist governments have led Argentina to a situation in which structural problems and not its governments are the ones “governing”. The country has not grown economically since 2011 despite the golden years of commodities that characterized the first Kirchner governments. An immense imbalance between the emphasis placed on redistribution and the mistreatment of production is at the base of the drama that this government is receiving. There can be no redistribution if there is nothing to distribute. The fundamental task of politics is about how to satisfy infinite desires with finite resources. Seeking to perpetuate itself in power, Kirchnerism deformed and trivialized the long tradition of affinity with the center-left that has long characterized broad sectors in Argentina. With its policies, it reversed the incentives, favoring nonwork (the “artful”) and harming work (the “giles”).

The expression of a resounding “enough” from the majority of the electorate in the face of an unbearable present and in favor of a change is a significant capital, although it could wear out quickly. The honeymoon could be short-lived if there is no didactic — almost Rousseaunian- communication effort to explain the medium and long-term objectives pursued by the initial pains, which will be important. It will not be possible to appeal to easy — or irresponsible- slogans, as happened during the electoral campaign. Social patience is not enough. In terms of policies, it will be necessary to think of processes of different temporalities that must take place simultaneously: to respond to the most pressing urgencies today, while reducing the fiscal deficit in the immediate future is only one of the multiple cyclopean challenges that emerge on the horizon.

Milei must, at the same time, satisfy the demands for which he was voted, as well as contain the protests of his opponents, not always democratic or peaceful. The fourteen tons of stone against the Congress during Macri’s term is a threatening precedent. As in Berensztein’s film, Argentina is facing a real odyssey. It appears that it will be very difficult — in what seems not only an economic problem but a cultural dispute —, for the elected government to respond to the delayed demands of the “giles” while including those sectors that, as a result of ill-conceived policies and lack of opportunities — along with an extensive and profuse narrative—, got used to conceive politics as the equivalent of an all-providing state and the economy as a realm of infinite goods. This seems to be an immense challenge. Governability, and even more, social peace itself, are at stake.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish