Two processes are taking place today that refer us to important flags of the feminist and women’s movement. We refer to the constitutional process in Chile and the bill for free and voluntary abortion in Argentina. The Chilean constituent will be the first constituent in the world that will have total gender parity, and the bill in Argentina responds to the commitment expressed by Alberto Fernandez to refer to the legislature an initiative that includes the demands of the movement for free, free and safe abortion.

President Alberto Fernandez’s initiative, which has already received half a vote of support from the legislature, is probably the most delicate because it deals with an issue that triggers a polarization of public opinion and opposition from the Churches and anti-rights movements (self-styled “pro-life”). Both with great influence in society. Gender parity as a concept has not generated that level of polarization, but the regulations designed for the Chilean constituent have an unprecedented character, which is surprising.

Both processes would qualify as examples of a “feminization” of Latin American politics. For this reason, we would like to say the following: there is an emergence of political positions that include issues mobilized by the feminist and women’s movement. These positions are not easy to come by in electoral and transition situations.

Unless they are political parties or movements with a clear institutional positioning in favor of the feminist narrative, the choices made by parties and movements that are more electioneering, catch-all or center, center-left, are often tinged with cost-benefit calculations that depend on the direction that public sentiment on these issues is taking.

The ability to affect those calculations and choices has always been one of the challenges of feminist pragmatics. Even President Fernandez, who seems to us to have a genuine commitment to the above-mentioned initiative, had to be pushed by the social movement. Peronism, being a very plural and varied political movement, cannot be considered a political actor that would certainly be allied with feminism, but there is currently a certain shift.

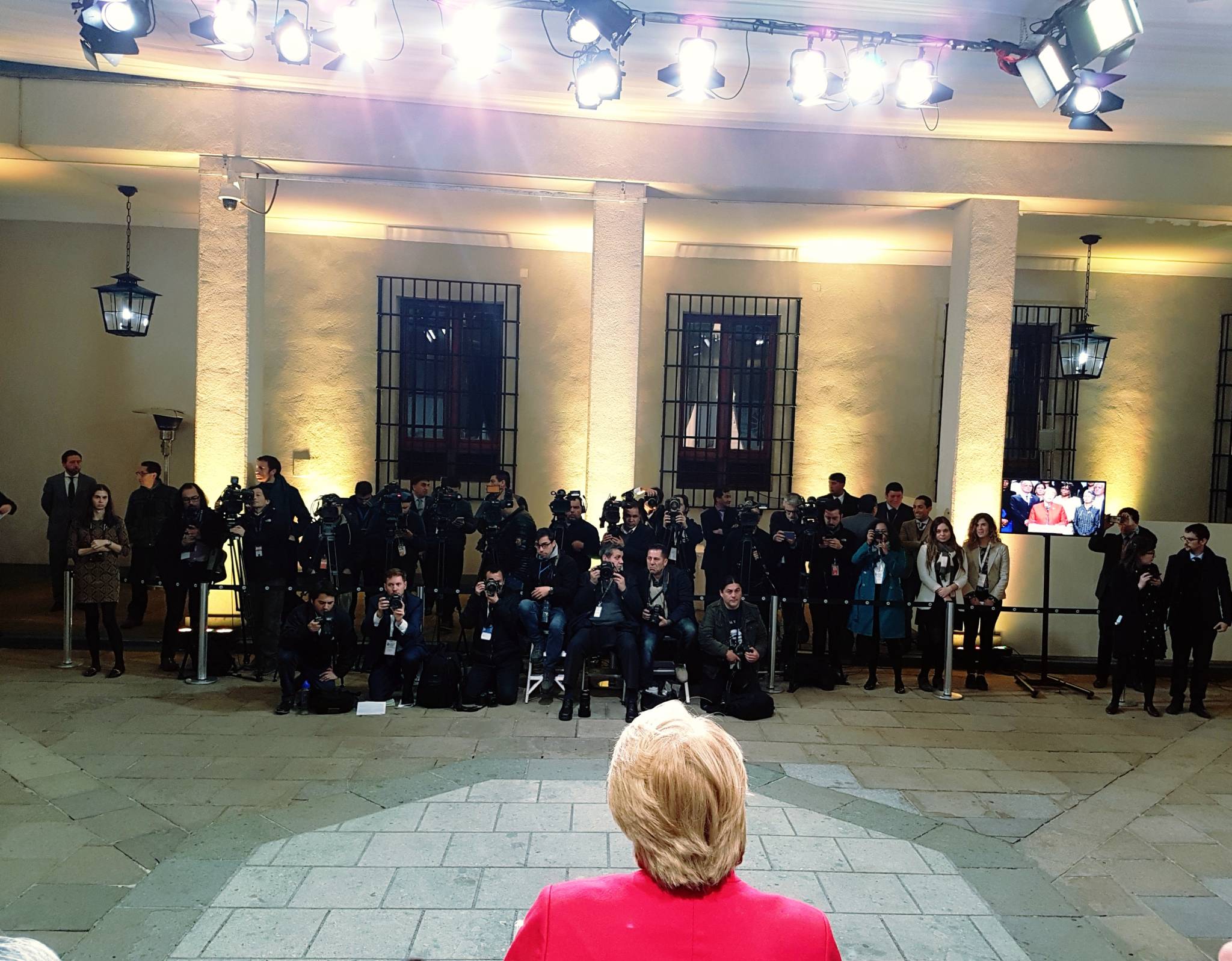

The Chilean initiative also reflects the strength of the feminist and women’s movement. Its protagonism in social demonstrations and protests was particularly noteworthy. Chilean politics, beset by a phenomenon that questioned its own representative function, moved towards this parity armor as a result of pressure from the social movement.

The question we ask ourselves is whether these two processes are a harbinger of what could happen in the new electoral cycle that is approaching, with elections in Ecuador, Peru, and Chile in 2021 and others in 2022. There are countries in which it is clearly unlikely that a feminization of politics, in the sense we are giving it, will emerge with any force.

Paraguay, perhaps one of the most conservative countries in the region, will certainly not build those bridges with the women’s movement. The Peruvian elections will be a new Pandora’s box, but one can expect new young actors to enter the scene carrying that flag. If the last municipal elections in Brazil are any indication, Bolsonaro’s misogynist and neo-fascist tone is likely to decline, but a centrism without major innovations in the area of gender policies will remain.

the palette of options brought about by the feminization of politics is quite broad.

Nevertheless, the palette of options brought about by the feminization of politics is quite broad. The 2017-2019 electoral cycle saw a shift to the right in the region, but still several important issues were well established and represented consensus along the political arc.

The generic concept of gender equality and the need to end violence against women were factors that virtually no one disputed. Equal pay and opportunities that give women a greater role in decision-making at all levels, as well as co-responsibility with men in domestic work and family care, were relatively stable parameters.

A breakdown in consensus occurred around issues related to sexual and reproductive rights, voluntary termination of pregnancy, and social and collective empowerment of the feminist movement. The famous “performance” of LasTesis about the “rapist in your way” and the accusing finger pointing at the State and systemic factors, are manifestations of autonomy and assertiveness that hurt the concessionary and patriarchal tone that the leaderships assume with respect to certain demands of women.

The more structural inequalities also caused significant opposition. For example, the whole debate on care and domestic work. The call for gender co-responsibility in domestic work as a private matter, resolved within the household, was one thing, but the valuation of unpaid domestic work and its inclusion in national accounts was another.

Feminism affects masculinity and views of it, the deeper aspects that clash with traditional patriarchal cultures

Culture and values are other decisive factors. Feminism affects masculinity and views of it, the deeper aspects that clash with traditional patriarchal cultures, or the practices of organized crime groups that somehow organize violent masculinity to exercise their dominance in certain territories.

Based on this experience, we will have to observe during the next electoral cycle if political positions shift to the right or the left of the palette of options brought about by the feminization of politics. Obviously, this process will depend a lot on the strength of the social movement and its ability to articulate a series of other demands and positions that demand equality and inclusion.

Although these are not defining aspects, we have no doubt that the engine of the movement will be significantly boosted if the Senate approves the initiative of the Alberto Fernandez government and if the performance of the Chilean constituent process demonstrates that gender parity adds value.

*Translation from Spanish by Emmanuel Guerisoli