Well-informed citizens with political knowledge rooted in objective facts have always been one of the preconditions for the existence and consolidation of a solid and robust democracy. For decades, the fine analysis of surveys on political culture found that a high cognitive capital in politics is associated with greater feelings of efficacy in making decisions, a predisposition to commit to public life, and a clear support for democracy over authoritarian alternatives. These findings, however, are challenged in times when the sources of the information on which this political knowledge is fed are subject to manipulation, fake news, and synthetic data production from artificial intelligence tools.

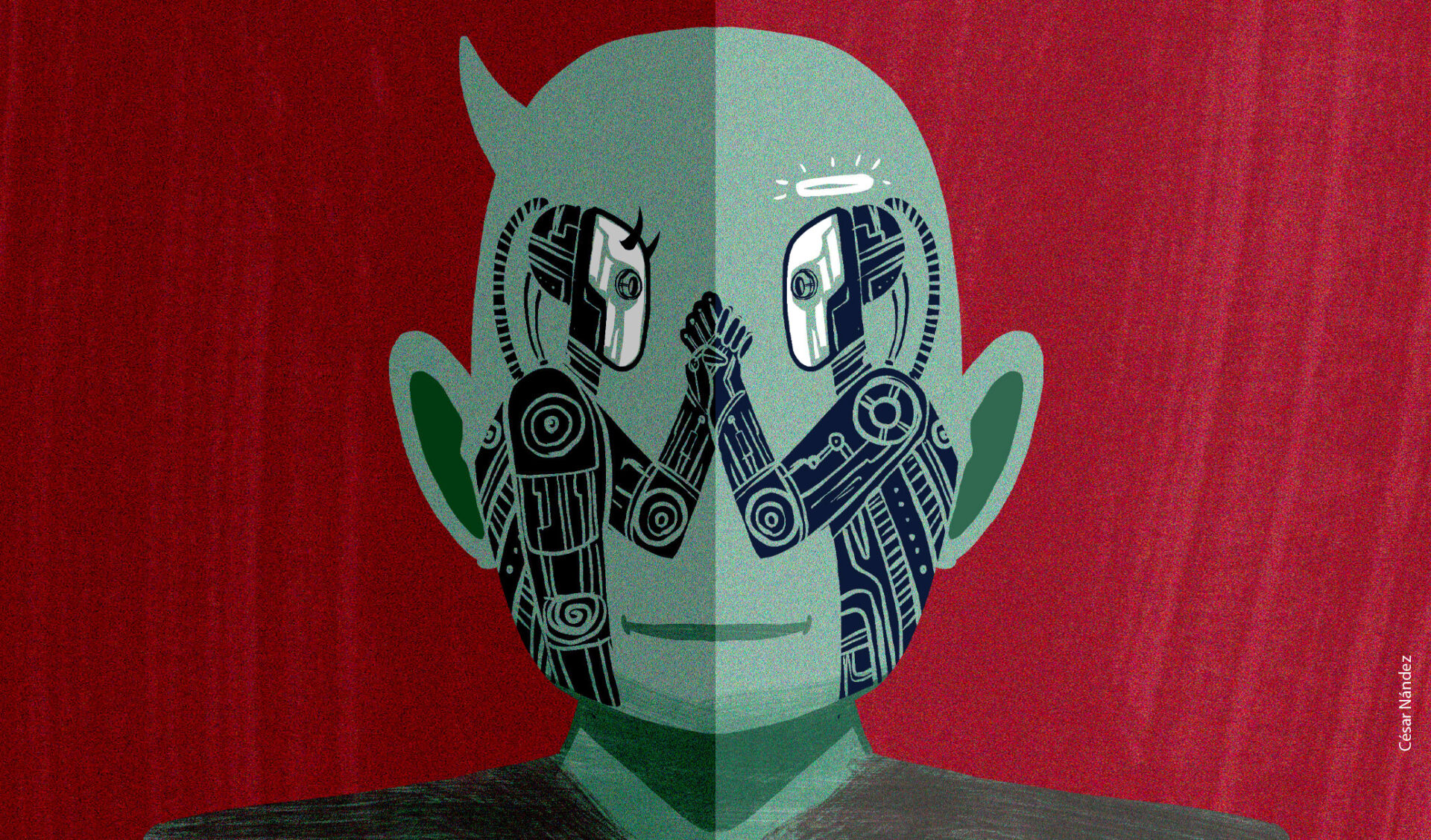

Can artificial intelligence be a lever toward a better representation of interests and a more effective way of governing and expressing citizens’ preferences, or is it a threat that risks distorting the quality of our public and democratic life? The tension between technology and politics is not new and there are illustrative cases of both encouraging forecasts and pessimistic conclusions.

Different interpretations

The Cambridge Analytica scandal, which laid bare the impact of social networks and big data in the manipulation of elections, symbolized the emblem of the pessimistic interpretation. The election of Donald Trump and the Brexit from Europe by the United Kingdom were its consequences. Without going so far away in geography and time, we have analogous examples applied to our region, especially Brazil, which is leading the process of discussion and intentions to regulate the new tools, such as artificial intelligence.

Amid the 2022 campaign, an extremely credible simulacrum of a well-known journalist of TV Globo announcing the results of polls that gave the victory to Bolsonaro was circulated. The video was intended to emphasize that the popular will supported the now ex-president, stimulating a climate of uneasiness among Lula’s supporters and a vote of shame in favor of the winner among the undecided. This example of “deep fake” illustrates the negative impact that some of the new technologies could have during elections, causing misinformation to circulate.

In contrast, more than a few commentators and industry leaders see the arrival of ChatGPT by the end of 2022 as an equalizing opportunity for information and data-backed decision-making for the vast majority. The accessibility of these artificial intelligence tools, from virtual assistants such as Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant to the most sophisticated generative models, such as Google’s Gemini and OpenAI’s recent ChatGPT-4 and Sora, favors the interpretation of AI as an instrument promoting transparency and the detection of bias or collective prejudice such as misinformation.

The ambiguous potential to facilitate as well as manipulate individual political decision-making processes is projected in the ambivalence as the public power is faced with the need to produce an AI regulation in Brazil. There are 46 different draft laws discussed at the federal level, seeking to control the impact that these AI tools have on politics and society.

Faced with the inertia promoted by bills that often contradict each other, the judiciary, through its electoral arm in the courts, decided to veto the use of “deep fakes” in campaigns under penalty of cancellation of candidacies and heavy fines. However, it has allowed the use of other AI mechanisms as long as they appear as such in the publicity and diffusions made by the campaign committees.

How do citizens react to positive and negative evidence on the effects of AI in public life?

A recent study by the consultancy firm Market Analysis reveals that Brazilians are not sure about the consequences of such tools. The doubts have to do with the production of disinformation: half of the interviewees are afraid that the dissemination of false news and lying or distorting data through AI could have a negative impact on Brazilian democracy. The other half believe that AI can help detect fake news and disinformative maneuvers.

Interestingly, higher levels of education and purchasing power do not increase the degree of confidence in exempting themselves from adverse influences for the reliable identification of news imposed by AI. The more educated and higher income electorate exhibits a degree of uncertainty about which information is true or false, and which images and videos are real or manipulated, similar to that of the less sophisticated or less affluent population.

When years of education and financial well-being do not give people a sense of greater control over what surrounds their lives and — above all — what shapes their impressions of reality and their political choices, we are in trouble. What do such circumstances tell us about the legitimate right to vote? And what other resources could moderate the paralysis in the face of uncertainty about what would be truth and information or in the face of temptations to intensify a climate of authoritarian extremism?

The ambivalence described above does not deny that Brazilian public opinion is inclined to a more optimistic reading of the effects of AI on democracy. Its main virtues would occur through an improvement in government transparency and access to information (55% think so). According to Brazilians, AI in politics would have more beneficial than detrimental results in facilitating citizen participation in political decisions and in helping to detect false news and disinformation.

At the same time, there remains moderate apprehension about its potential negative impacts, such as the dissemination of disinformation and fake news in more sophisticated forms such as “deep fakes” (48% feel this way). Much lower is the fear that AI will lead to increased concentration of power in the hands of unelected organizations or entities (31% are wary of this), decreased security and trust in elections (28% fear this), and reduced transparency in government decisions (28% feel this way).

These perceptions change significantly according to age: younger people are more likely to recognize the positive impacts of AI on democracy. Skepticism grows with age suggesting that the experience of access to information and the workings of electoral routines, rather than generating a sense of empowerment and control, intensifies the sense of powerlessness or — at the very least — recognition of the complexity and lack of comprehensive understanding of the role of high technology in politics.

There are many challenges to harmoniously and organically integrating artificial intelligence into the institutional processes and political engineering of our democracies. To begin with, there is no consensus regarding its advantages over its threat potential. This double-edged sword reading will condition possible innovations, as well as fuel demands for external regulation. The optimism of the new generations, especially digital natives, is no guarantee of a supportive bias in the near future. On the other hand, the fear persists that such sympathy is more an expression of naivety than of identification and exploitation of palpable benefits. The promise of better governance and citizen inclusion from AI is still a pending task.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish.