Coautor Eduardo Ryo Tamaki

Contexts of crisis are fertile ground for anti-system candidates. On August 13th in Argentina, during the obligatory primaries (Primarias, Abiertas, Simultáneas y Obligatorias, or PASO), Javier Milei, an extreme right-wing populist candidate, came out first with 30% of the votes, leaving the opposition coalition Juntos por el Cambio in second place and the government coalition in third. In a context of rampant inflation, exchange rate disparity, and rising poverty, the 7 million who supported Milei primarily expressed frustration and anger towards the traditional political offerings in the face of the economic situation that the current government and its predecessor clearly failed to address. To counter what he defines as “Kirchnerist populism” or “leftism,” Milei proposes an economic program at the opposite end of the spectrum, based on minimal government intervention and a balanced budget, claiming that the “political elite” will bear the cost of change, not the people. His proposal is quite populist.

In fact, Milei has proven to be a classic example of populism. It’s worth noting that populism is not necessarily tied to economic policies, although it traditionally was associated with fiscally irresponsible governments. According to newer perspectives, populism is best defined as an ideology, albeit a weak or incomplete one, a loosely articulated set of ideas about the world and politics that are expressed and sustained through discourse. It’s a black-and-white worldview that pits a morally virtuous and homogenous “us” or “people” against a malevolent, corrupt, and self-serving “them,” an “elite” that has exploited the “people,” usurping their “power” to pursue their own interests. The populist seeks to mobilize the population against these elites (economic, scientific, political, or even transnational) while promising to restore power to the people.

Milei embodies all of this, boasting 1.4 million followers on TikTok, where he captures them with his narrative of “us” against “them,” the thieves who have looted the system and are consequently responsible for 40 years of failures in Argentina. If he takes office, he promises to eradicate the privileges of politicians and put an end to the parasitic, corrupt, and useless political caste. Only then can the Argentine people be free; only then can Argentinians be architects of their own destiny.

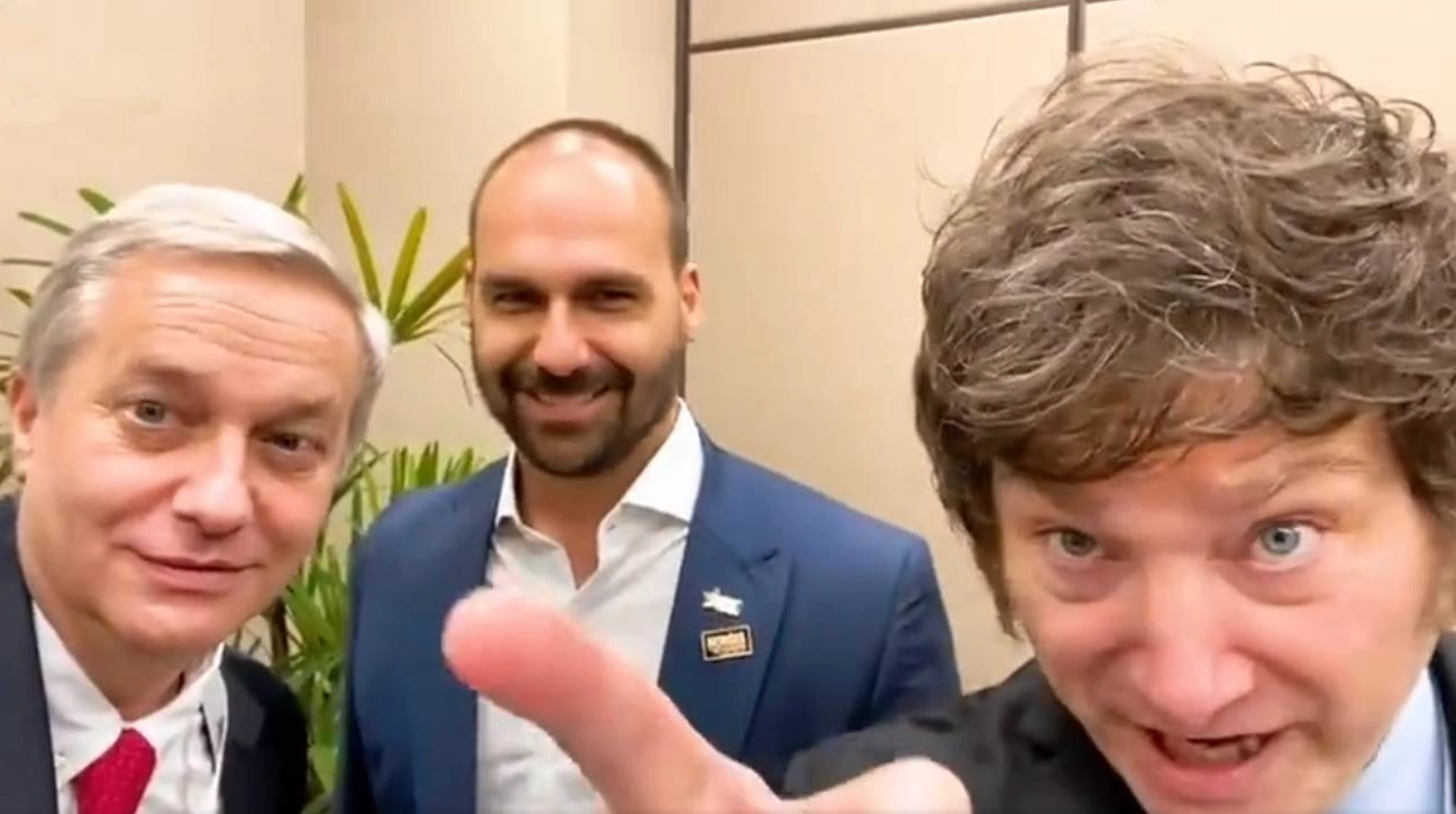

Milei is not a new or isolated phenomenon. The “Trump of the Pampas” would be equivalent to the “Trump of the tropics,” as Bolsonaro has often been referred to. Indeed, these three leaders share many similarities: Milei also wages a moral crusade against progressive and liberal values which, in his view, seek to undermine and destroy the concept of family. In this sense, he shares Bolsonaro’s anti-communism/socialism agenda. Asserting climate change denial, Milei claims that it’s a socialist lie and believes that sex education is a post-Marxist agenda aimed at exterminating the population. What’s more, following in the footsteps of Trump and Bolsonaro, Milei has also promised to move Argentina’s Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. Within Latin America, Milei is another expression of the rightward shift that has given rise to populists like Rodolfo Hernández in Colombia, Keiko Fujimori in Peru, and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, among others.

Why Should We Be Concerned About Milei as President?

A week after the PASO, there were looting and vandalism incidents in various parts of the country, a familiar story in Argentina. If the economic situation doesn’t improve and social conditions worsen, President Milei is not an unlikely scenario. Here we see another problem that goes beyond ideology: the populist, often an outsider or rebel, who is seen as bringing a “breath of fresh air” to politics, lacks a political structure of their own and is also hostile to cooperation, coalitions, and concessions.

To illustrate, it might be worth contrasting with a case from recent Argentine history, that of Carlos Menem, president from 1989 to 1999, who came to power promising high wages and a productive revolution, only to embrace neoliberalism after his election. Milei not only asserts that Menem’s first government was the best in history, but also claims to have been blessed by the former president as his successor. Beyond similar agendas of inflation control (convertibility in the former case, dollarization in Milei’s proposal) and reducing the state’s role, Menem stood out for implementing one of the largest privatization policies in the region. He positioned himself as an outsider option to attain power when he was actually the legitimate leader of the traditional and majority Justicialist Party, which not only secured the presidency but also majorities in both legislative chambers, granting him two fundamental laws of legislative delegation in 1989 and many more throughout his first term.

In a democracy, governance doesn’t solely rely on public opinion. To pass important reforms like privatizations or central bank closure, institutional support is needed. President Milei’s support in Congress will likely be meager, and he will inevitably have to compromise with the “establishment.” Two possibilities emerge here. The first, reminiscent of Bolsonaro, who ascended to the presidency with a notable minority in parliament, promising grandiose pledges to eliminate the ‘old politics’ and not ‘engage in politics’ with the corrupt establishment. Once in power, burdened by mishandling the pandemic and facing numerous impeachment requests, he ended up striking a deal with the “centrão,” which means distributing ministries and resources to this group of opportunistic parties. Recall that Bolsonaro left office with a high cost for democracy, questioning electoral institutions and, like Trump, with a January 8th assault on all three branches of government in Brasília.

The other alternative is well-known in Argentina. A radical or intransigent president will face resistance in Congress, leading to a clash of powers. In a crisis context, protests in the streets would intensify, resulting in another interrupted presidency. The prospects remain uncertain even for the October 22nd elections. Amid threats to democracy and economic risk, Milei’s populist offering has cast a shadow over what should be a celebratory year, one in which Argentina commemorates forty years of democracy.

Eduardo Ryô Tamaki is Research Fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) and a member of Team Populism.

*Translated by Ricardo Aceves from the original in Spanish.