Venezuela has quickly gone from the ridiculous to the grotesque, all while the deep crisis experienced by millions of Venezuelans worsens. On July 5, in a military parade to commemorate the country’s independence, an inflatable doll called “Super Mustache” replaced President Nicolás Maduro, who was absent from the most important public event of the patriotic calendar. On the following day, a horrifying crime made headlines: a Chavista leader who, after disappearing from the public two years ago, was found dismembered by the order of his wife to prevent him from accusing her of corruption. But while this grotesque news is being disseminated, leaving a large part of the population indifferent, the decay of the public health system is hitting the most vulnerable Venezuelans.

The disaster of the Venezuelan healthcare system has been evidenced in the compilation of the HumVenezuela platform and by the National Survey of Hospitals, civil society initiatives that seek to fill the information vacuum left by the Maduro regime.

The Ministry of Health has not published the national epidemiological bulletin since May 2017, when the report for the last week of 2016 was disseminated. At that time, the bulletin snuck into the media and revealed that the infant mortality rate had skyrocketed: 11 466 children died in 2016, a 30% increase compared to 2015. This cost the then Minister of Health, Antonieta Caporale, her job. Since then, there has been no official epidemiological data.

The drama at the children’s hospital

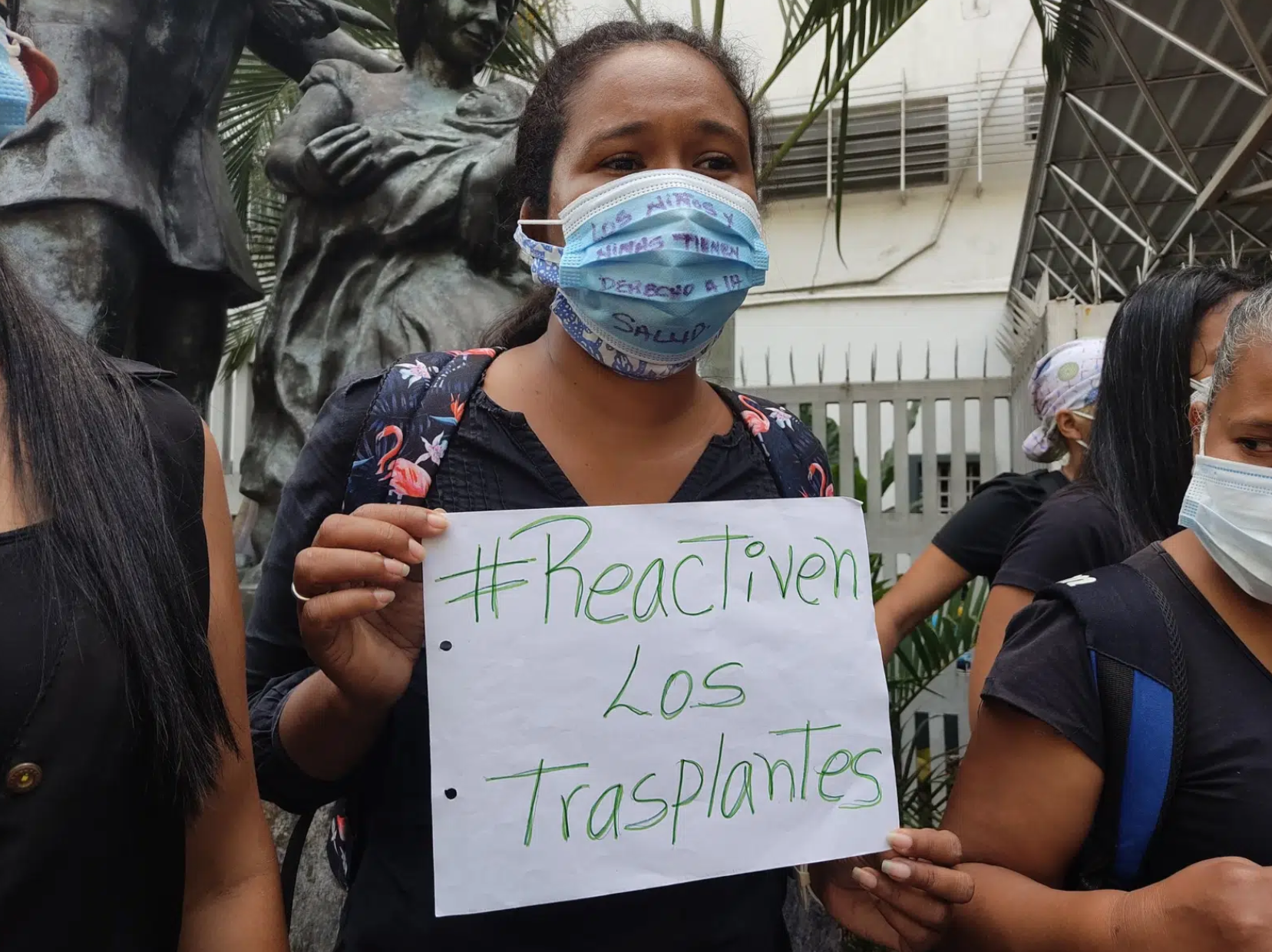

Two reports prepared by the non-governmental organization, Prepara Familia, document the situation in the country’s main pediatric hospital in Caracas, the J. M. de los Ríos. As a sign of the tragedy, one of the reports mentions the impact of the suspension of the organ transplant program as of June 2017, which, according to NGO estimates, has affected some 1500 people, including 150 children and adolescents still waiting for an organ to save their lives. Maduro himself announced in November 2021 that the national transplant program would be reactivated, but this has not happened as of yet.

The most illustrative case of this transplant crisis is that of the nephrology unit of the J. M. de los Ríos Hospital. Since 2017, 71 children and adolescents have died due to a lack of antibiotics and problems with dialysis equipment. The National Association of Nephrology estimates that, since the suspension of the transplant program, more than 70% of the dialysis units do not function properly due to equipment defects and the lack of potable running water, among other problems.

The hemodialysis unit of the national pediatric reference hospital is the only one in the country that can offer the service to children weighing less than 10 kg. Only half of the machines are working, according to the report. The hospital does not have a CT scanner or MRI equipment. The craniotome, an instrument to perform brain operations, does not work due to lack of maintenance. The pediatric center only has a portable X-ray machine, which is not working most of the time. The laboratory has no reagents, so patients and their families must resort to private laboratories. And the nephrology laboratory unit has been closed for five years.

Even in the face of death, this hospital does not have adequate services. The poor conditions of the anatomical pathology unit do not allow for proper care of corpses, especially when several deaths occur in a short period of time. Families receive no support from the hospital administration or the government and rely on the help of civil society organizations to cover funeral expenses.

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation substantially. The country’s pediatric units, including the J. M. de los Ríos hospital, have given priority to minors with symptoms, which has had a negative impact on patients suffering from chronic diseases and nephrological, hematological, and cancer conditions.

The report also points out that 95% of the people accompanying hospitalized children and adolescents are women, which demonstrates the enormous gender inequity. Care tasks are carried out by mothers, other female relatives, or those close to the patients who do not receive any type of support from the health services. Therefore, the report considers it important that this work be remunerated to support women and families who come from the poorest sectors of society.

Fundamental rights violated

The general health context in Venezuela is one of continuous deterioration. In the midst of a pandemic, data coming from non-governmental organizations reveal chronic problems that are worsening. According to the most recent report of the National Hospital Survey of June 2022, the rates of lack of basic supplies is 47% in the emergency rooms of public hospitals and 72% in the operating rooms.

For its part, the HumVenezuela report, which was published in June 2021, points out that with the pandemic, the number of Venezuelans who lost health services, both in the public and private systems, rose to 18.8 million. It also increased to more than nine out of ten people who are lacking financial protection and to almost six out of ten those who did not have financial resources to cover health expenses. Public hospitals reported 82% inoperability to treat diseases other than COVID-19, a situation that is aggravated by the retirement of between 58% and 70% of medical personnel and 62% to 88% of nursing personnel. Specialized health personnel are emigrating like millions of other Venezuelans.

Prepara Familia and other civil society organizations have repeatedly denounced this situation before international bodies because the Venezuelan Attorney General’s Office and the Ombudsman’s Office, agencies that should ensure the defense of the rights of Venezuelans, have turned a blind eye to the petitions of those affected and those who represent them.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) has issued several precautionary measures to protect the patients of the J. M. de los Ríos pediatric hospital. And although the propaganda of the Maduro regime pretends that “Venezuela is fixed,” the children who die as a result of a lack of medical care would likely disprove of a slogan that sounds like an insult to their memory and the pain of their families.

Translated from Spanish by Alek Langford