The midlife crisis represents a period of personal questioning that appears when we pass from youth to maturity. It is usually characterized by a feeling of frustration, due to not having fulfilled self-imposed life expectations or those imposed on us by society itself. This metaphor could very well represent the (not so) young Argentine democracy, about to turn 40 years old next December 10.

The Argentine democratic cycle (1983-2023): a bittersweet balance sheet

Argentina’s democracy has shown ample signs of resilience over four decades of institutional development, having weathered the military crisis between 1987 and 1990, the economic crisis between 1989 and 1991, and the social crisis between 2001 and 2002. All these tests were, to a greater or lesser extent, satisfactorily overcome.

This fact deserves to be highlighted because, since the enforcement of the so-called Saenz Peña law in 1912, which established the universal secret and compulsory nature of suffrage, the institutional life of Argentina until 1983 had alternated between military, civil-military, democratic regimes without republican content, republican without democratic content or semi-democratic regimes.

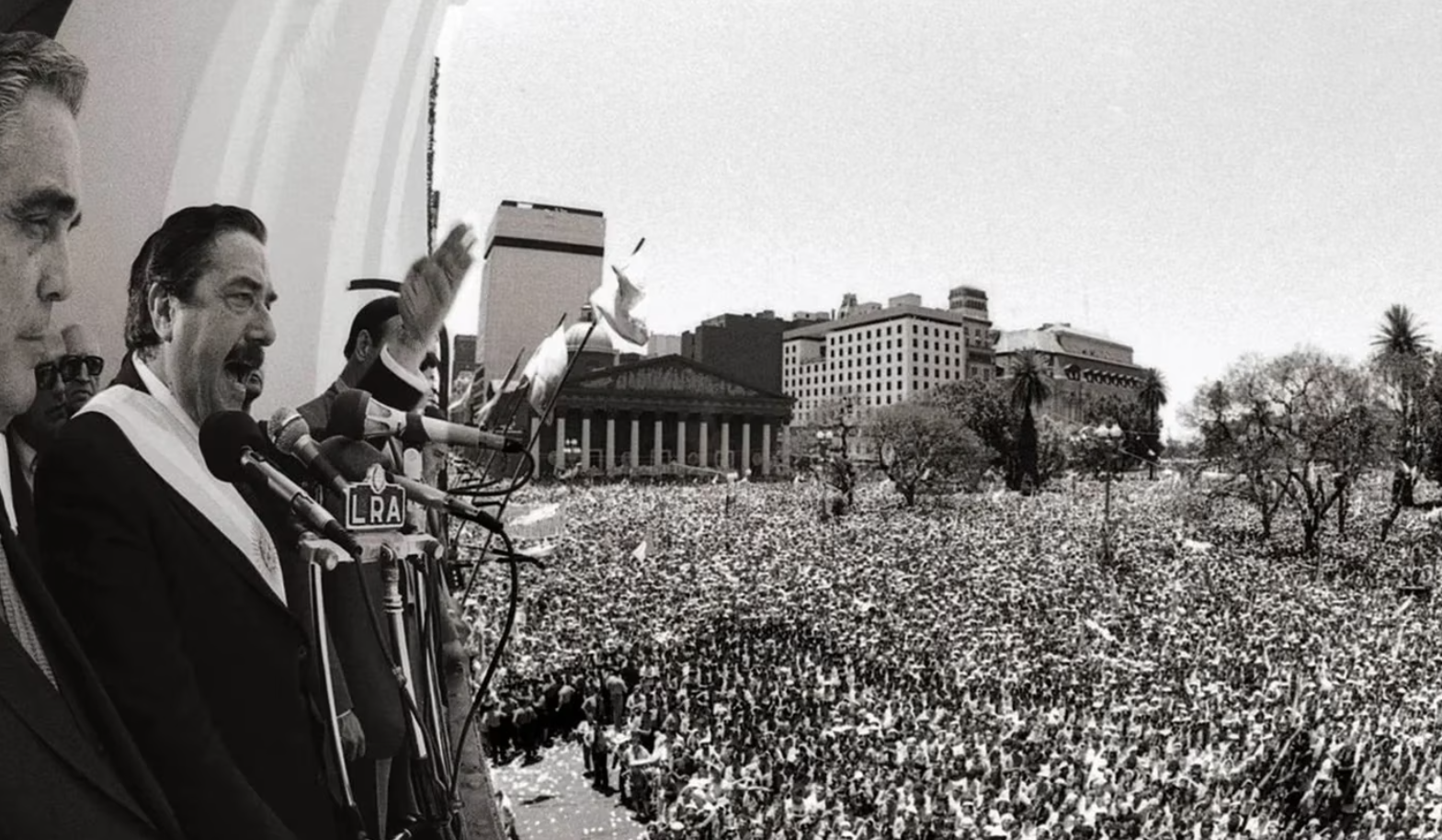

Nevertheless, this long cycle exposes us to a modest balance in terms of the satisfaction of social expectations. This has been a process of few achievements (a resilient democracy, a growth of the agenda on civil rights of a different generation) that coexists with many frustrations in relation to that hope of a political regime that had the capacity to satisfy multiple demands, which was synthesized in the slogan “With democracy we eat, we cure, and we educate”, so present in the campaign message of the candidate Raúl Alfonsín in 1983.

The increase in poverty, the ever-growing levels of social inequality, and the increase in urban insecurity highlight the difficulties in fulfilling the reparation promise made in that distant (and so close at the same time) 1983.

This long period of democracy has coexisted and still coexists with a long cycle of emergency that began in 1989 and has lasted until today with some brief interregnums between 1999 and 2001, and from 2015 to 2018. Democratic Argentina has lived in an (almost) permanent emergency, to paraphrase the Argentine political scientist Hugo Quiroga.

Between democracy and emergency

The 1989 presidential replacement (the first stage of the emergency of democracy) took place in an unprecedented context in contemporary Argentina. For the first time in the discontinuous constitutional history of our country, power was handed over between presidents of different political parties: Raúl Alfonsín, for the Unión Cívica Radical, and Carlos Saúl Menem, for Justicialismo. The sociopolitical context, marked by a terminal economic crisis (hyperinflation), a social crisis (looting), and a crisis of the state model that had been implemented since World War II, forced the radical leader to hand over power early.

The combination of a fragile electoral coalition, based on unstable agreements and in the midst of a recessive domestic economic situation, with fiscal restriction and exchange rate rigidity (and a financial environment not very available for cooperation), as well as a social rebellion led by popular and middle sectors, were the main factors that led to the crisis at the beginning of the century in Argentina. A crisis that culminated with the resignation of Fernando de la Rúa on December 20, 2001, and the beginning of a new stage of emergency.

At the beginning of 2020, Argentina’s democracy had to face a new emergency, this time as a result, of no longer an economic catastrophe as in 1989, or a social one as in 2001, but of an international health crisis, due to the pandemic declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO).

As a result of the health crisis, the Argentine economy was one of the hardest hit, along with Peru and Venezuela, with a fall in GDP above the regional average during 2020. The prolonged quarantine had poor results, in addition to the transgressions from the highest presidential authority (“Olivosgate”). The vaccination campaign was ineffective and had cases of open violation of the most elementary principle of equality before the law (“Vacunatorio VIP”) and the prolonged closure of educational activity, partially compensated with virtual teaching at different levels, which implied an educational gap for a whole generation of students.

To the deficient results mentioned above, we must add the failure of the Argentine president to keep his promise to establish a more cooperative relationship with the opposition and, consequently, a new political climate: the aforementioned balance allows us to affirm that this crisis was an opportunity, but wasted, for the government of Alberto Fernández.

And yet…

Before this balance of achievements, limitations, quasi-chronic emergency, and unfulfilled expectations over forty years of Argentina’s democracy, we can (and should) still say, as Norberto Bobbio did in his famous essay “The Future of Democracy”: “and yet…”.

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva