Bolivia’s election results, beyond triumphalist or fatalistic interpretations from either side of the ideological spectrum, signal two key points. First, that the country’s liberal institutions still maintain a degree of health, and second, that the economy exerts a tremendous influence on the political configuration of the nation.

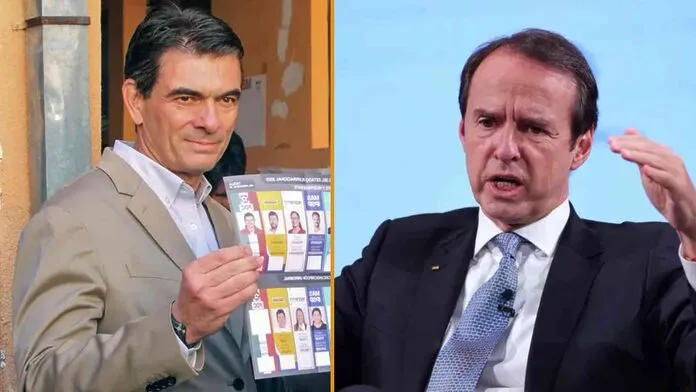

In what resembles a second chance for Bolivia’s traditional political elite, a former president (Jorge Quiroga) and the son of a former president (Rodrigo Paz) are competing in the second round. Regardless of who wins, the country’s political future will depend on how the Bolivian elite addresses the profound economic problems and manages to generate growth and social inclusion.

From chronic instability to the rise of the MAS

These challenges are not new. Bolivia has long been considered one of the poorest and most politically unstable countries in Latin America. According to data from the Cline Center for Advanced Social Research at the University of Illinois, Bolivia holds the dubious distinction of being the country with the most coups d’état in the region, with more than 40 since 1947—including both failed and successful attempts. Individually, it even surpasses any African country in this category.

During the 1980s and 1990s, following a turbulent period marked by both right-wing and left-wing military dictatorships and an economic crisis, including hyperinflation under the leftist Democratic and Popular Unity (UDP) government, the political system coalesced around three parties: the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR), the conservative Nationalist Democratic Action (ADN), and the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR).

At the time, none of these parties managed to secure an absolute majority, typically earning between 20% and 30% of the vote, which made parliamentary coalitions indispensable for governing.

However, the poor results of privatization policies in the late 1990s and early 2000s eroded those modest gains in political stability. This paved the way for Evo Morales, a coca growers’ union leader, who successfully channeled protest votes and frustration with the traditional political elite through his party, the Movement for Socialism (MAS).

Morales’s victory in 2005, with more than 50% of the vote, was surprising and became the most decisive in Bolivia’s recent political history. His legitimacy allowed him to convene a Constituent Assembly in 2009 and transform the Bolivian state into a Plurinational one, in a context highly favorable due to the commodity boom fueled by China’s demand.

Evo Morales: a cycle of hegemony and downfall

The reforms expanded Indigenous representation and extended presidential powers. The higher judiciary began to be chosen through popular vote. During this period, Morales’s hegemony was absolute, and many political scientists classified his regime as a form of electoral autocracy or competitive authoritarianism.

Yet, the restriction on indefinite reelection proved to be a key stumbling block, highlighting the importance of institutions and their ability to shape political behavior. Morales attempted to bypass this barrier with a 2016 referendum, in which voters rejected his bid. Nonetheless, the Constitutional Court later approved his candidacy, a move widely questioned.

The crisis that ultimately forced Morales from power began during the 2019 election vote count. After a contentious campaign, when early tallies pointed to an unprecedented runoff, the preliminary results system was suddenly suspended. When it resumed, Morales appeared as the outright first-round winner, sparking allegations of fraud. A report by the Organization of American States identified significant irregularities, triggering a political crisis that ended with Morales’s resignation, backed by senior military officials.

Although MAS seemed delegitimized, the poor performance of interim president Jeanine Áñez and the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic revived it. Legally barred from running, Morales endorsed his former economy minister, Luis Arce, who was elected in 2020.

Nevertheless, Morales’s shadow lingered. His ambition to return to the political center led to clashes with Arce and the MAS itself, which he eventually left in February of this year after encouraging protests against the government and even issuing veiled threats of civil war. The founding of his new party, Evo es Pueblo (“Evo is People”), underscored the personalist and caudillo-like dimension of his leadership, despite former vice president Álvaro García Linera’s efforts to portray him as a representative of social and Indigenous movements under the premise of “governing by obeying.”

Economic crisis, runoff election and an uncertain future

Under Arce’s administration, the economic crisis deepened: inflation between 20% and 25%, fuel and dollar shortages, nearly depleted international reserves, and a fiscal deficit close to 11% of GDP. Hydrocarbon production plummeted, and despite being a major gas exporter, Bolivia increasingly relied on imports. In this environment, a failed coup attempt was launched in June 2024 by General Zúñiga.

Ultimately, the economic and political crisis shattered MAS’s two-decade-long hegemony. Its collapse was monumental: its candidate received barely 3% of the vote and the party lost all representation in the Senate. Meanwhile, null votes reached around 18%, a record figure driven by Morales’s call to abstain. A runoff election was called for October, something unprecedented since Bolivia’s return to democracy.

The country’s political future remains uncertain ahead of these elections, but two decisive questions stand out. First, whether the new government will be able to stabilize the economy and reignite growth without triggering destabilizing social tensions. Second, what role Evo Morales will play—whether his new party will attempt to regain prominence by combining disruptive social mobilization with electoral participation, as in the past.

Whether Bolivia’s political elite can overcome short-term interests to secure the country’s future will be crucial.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.