Sometimes the electoral game reaches its peak when the issue to be decided becomes simplified. Faced with a scenario in which multiple options compete, each loaded with its own level of complexity, the situation that opposes only two possibilities proves to be more efficient. If, in addition, high doses of emotion are added, the outcome can be even more impactful.

Among the range of electoral processes, those that involve a consultation where only a “yes” or “no” answer is possible belong to this category. It also occurs when the decision is to be made between individual candidates. Moreover, when the prevailing logic is that of an absolute majority, which normally forces a final confrontation between two contenders, the issue becomes even clearer. In each of these situations, the opposing positions combine a plurality of circumstances — personal traits, political programs, the careful crafting of convincing narratives, socioeconomic context, and more — that shape the options upon which the electorate must base its succinct decision. Nor should the constituents of the demand itself, their legacies, and their environment be overlooked.

Since their independence, the countries of Latin America have seen how the assessment of the role of the United States has been a fundamental factor in shaping the political identity of their societies. Antagonism has been a constant feature that has often defined the decisive character of political struggles. The work Ariel by the Uruguayan José Enrique Rodó, the Ode to Roosevelt by the Nicaraguan Rubén Darío, and Anti-Imperialism and APRA by the Peruvian Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, among others, at the dawn of the 20th century, laid the intellectual foundations for the confrontation that would intensify during the Cold War. Then, milestones such as the triumphs of the Cuban and Nicaraguan revolutions, the spread of the doctrine of national security among regional armies with the backing of various coups d’état, the invasions of the Dominican Republic and Grenada, and the Torrijos–Carter treaties defining the handover of the Panama Canal to the country that had gained independence during its construction, all deepened this dynamic.

In 1946, after a long decade of military tutelage and social mobilizations amid profound transformations — and having moved beyond the global wartime context — Argentina held elections. A talkative military officer, socialized in Benito Mussolini’s Italy thanks to his diplomatic post there, with ministerial experience in a military government that had allowed him to put into practice a blend of statist programs with certain social and nationalist components, emerged as a candidate with a real chance of winning. His growing popular appeal was countered by the activism of the U.S. ambassador to Argentina, who, echoing the Truman administration’s stance, saw him as a threat to the new international order then taking shape.

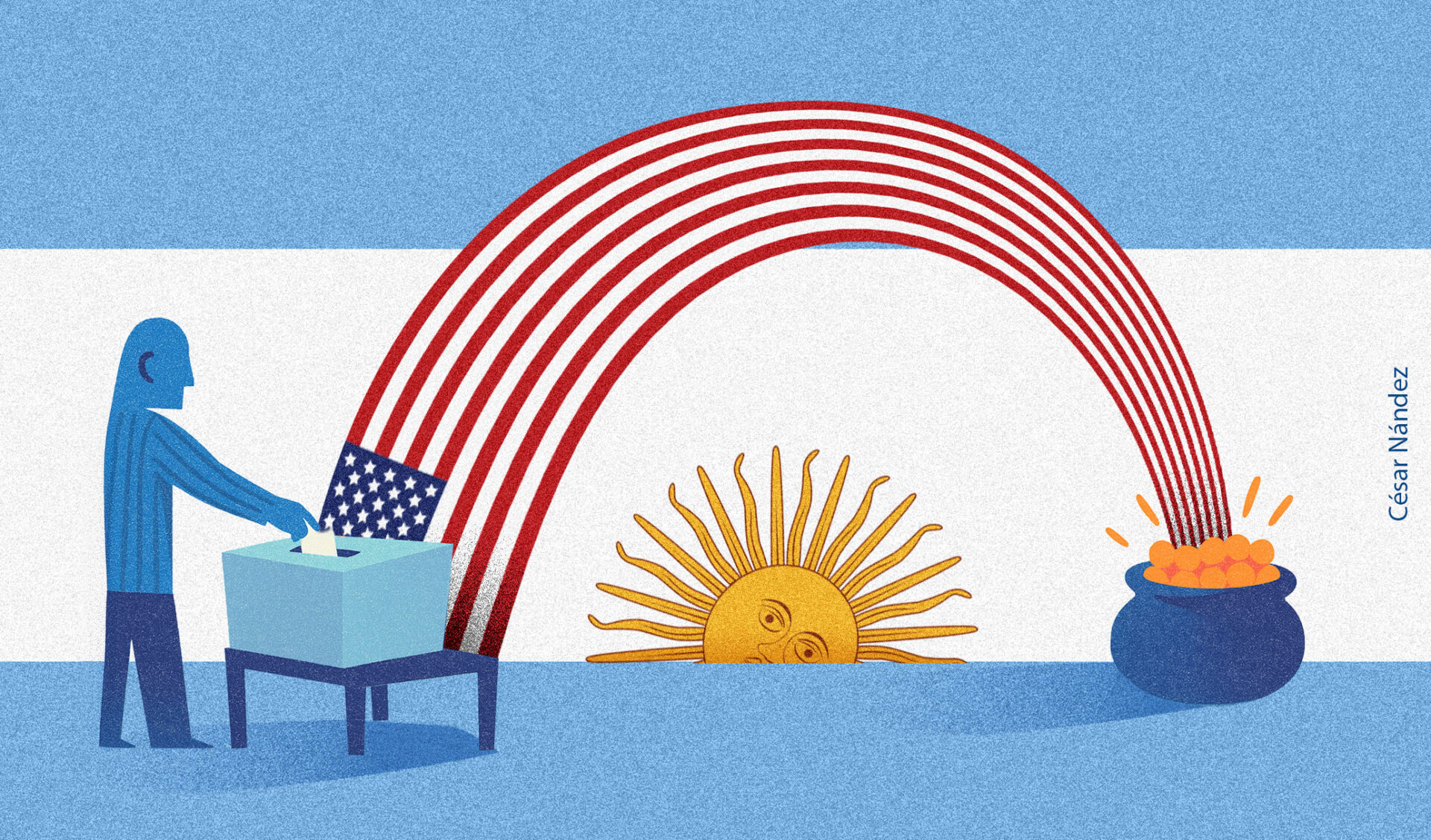

Juan Domingo Perón was that presidential hopeful, and Spruille Braden the American diplomat. It mattered little that Perón’s opponent from the Democratic Union was a well-known politician and that his coalition enjoyed broad support across the spectrum opposed to the military dictatorship. Perón managed to impose in his campaign the narrative that would ultimately lead him to a clear victory. He simply drew upon the anti-American sentiment that had simmered in prior decades — fueled by the ideas expressed in the works mentioned above and by reaction to Washington’s policies of “manifest destiny” and “the big stick and the carrot,” heirs to President Monroe’s proclamation. “Braden or Perón” became the winning slogan that Perón posed to Argentine voters to rally them around his cause.

Eighty years have passed, and that slogan seems to regain its relevance ahead of Argentina’s legislative elections this Sunday, the 26th. The alliance between Javier Milei and Donald Trump, grounded in the shared sympathy of two narcissistic showmen with common values surrounding libertarian capitalism — and complementary needs: Argentina’s battered finances and the U.S. interest in curbing Chinese presence while securing Argentina’s rich mineral deposits — has led to an unbearable level of interference by the northern country in the southern nation’s electoral process.

The American friend appears willing to invest enormous sums in the Argentine economy. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, has announced a $25 billion investment to build a data center in Argentina’s Patagonia region. For its part, the U.S. government is reportedly prepared to contribute another $20 billion to Argentina’s coffers through an unusual financial mechanism. But in this case, there is a crucial condition: Milei’s option must win — or at least achieve an honorable electoral result that allows him to continue the political program designed in the Casa Rosada. Otherwise, the White House will withdraw its support, and Argentina may once again slide into one more of the crises that have plagued it for half a century. The dilemma thus seems to be reborn — but this time, it is not “Trump or Milei.” How will Argentine voters process it? Trump and Milei against national sovereignty?

However obsolete this concept might seem today, President Trump’s authorization of covert actions on Venezuelan territory marks a step forward in a strategy inaugurated with an attack that caused the deaths of around twenty people and the destruction of at least five boats allegedly carrying drugs in the Caribbean — that quintessential sea defining the U.S. backyard. A lamentable and agonizing epitome that sketches an unmistakable path toward an old polarization, now reestablished. This situation is gradually shaping the Latin American political landscape — something already visible in Brazil, where President Lula da Silva has earned evident public support for his firmness in confronting the U.S. government.

*Machine translation proofread by Janaína da Silva.