Finally, the polls were right and former minister Rodrigo Chaves, of the Social Democratic Progress Party, was elected as the new president of Costa Rica. Chaves obtained 52.9% of the votes against 47.1% for José María Figueres, of the National Liberation Party. Despite the calls of attention about Chaves’ confrontational behavior, most of the population, upset with the status quo, has considered that his defiant ways are more likely to change the country’s situation.

The former minister has won just over one million votes and has outnumbered his opponent by more than 100,000 votes. Abstention stood at 42%, only 2% more than in the first round of these elections. Looking at the territorial distribution, Figueres has managed to slightly surpass Chaves only in the provinces of San José and Cartago, while Chaves has won comfortably in the remaining five provinces. This is related to the perception that the rupturist candidate has clearly captured the rebellion of the common people against the elites that the studies have registered in recent years.

Of course, remaining political forces could have united to prevent the risk of the confrontational candidate’s victory, but their resentment towards José María Figueres has prevented them from doing so. In fact, none of the parties that have managed to reach the Parliament called to vote for National Liberation Party. This, although in the last week a significant number of political personalities of different sign made declarations against Chaves.

Everything indicates that the electoral bases have not paid attention to them, as can be seen from the fact that in the two port provinces, Puntarenas and Limón, where Chaves had obtained a low electoral result in the first round, he has now obtained his best results. It seems evident that the voters of the other parties have clearly inclined towards Chaves this time.

Rodrigo Chaves’ victory has provoked immediate reactions of uneasiness in sectors of the Costa Rican political class. Heading a recently created party, without a known government team and willing to overcome the institutional obstacles that prevent from acting to face the crisis, the new president is perceived as the incarnation of uncertainty.

For its part, the feminist movement does not forgive the accusations of sexual harassment that Chaves faced when he was a World Bank official. On the eve of Election Day, this rejection was reflected in several major U.S. newspapers. Chaves responds that this happened 14 years ago, that he was never formally convicted, that he has already learned the pertinent lessons and, above all, that it is not fair to condemn him forever. In any case, it is evident that the majority of men and women, when casting their votes, have given less weight to this remark than to their perception that Chaves will be able to confront the status quo.

There are even observers who point out that the insistence on this issue has ended up benefiting the candidate. The well-known journalist, Pilar Cisneros, currently elected deputy for Chaves’ party, includes this issue as one of the many personal attacks that the economist has faced. On the other hand, an important segment of the conservative Costa Ricans, formed by the religious sectors, seems to have expressed with its vote the resentment it shows towards the so-called “gender ideology”.

However, for many voices in cultural and political circles, this issue damages Costa Rica’s international prestige as a country that is a standard-bearer of various humanist causes. However, the grassroots Costa Ricans seem to have other more prosaic concerns, besides evidencing a liver that has been swelling over time. That is why they have opted for the candidate who seemed to understand their discomforts more clearly.

The other pending repercussion that the new president will face is related to the investigation carried out by the Supreme Tribunal of Elections (TSE) regarding a package of undeclared financing for his electoral campaign. If at the conclusion of the investigation the TSE sees evidence of a crime, it will have to pass the case to the ordinary justice, which will initiate a process that could eventually disqualify Chaves or some of his collaborators. Something unlikely but not impossible.

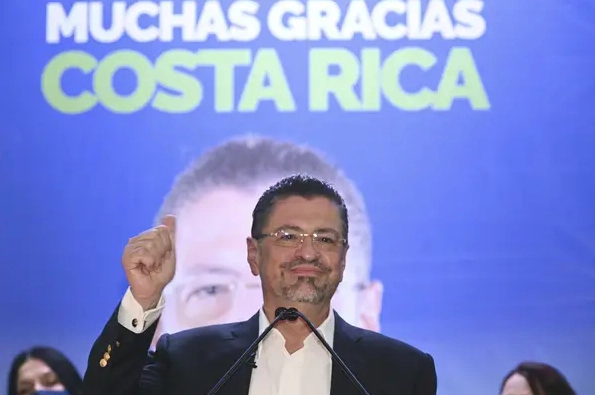

After knowing the results, in his first speech of gratitude, Rodrigo Chaves has changed the tone of his speech, emphasizing the need to abide by the current regulations and highlighting the collaboration and consensus with the other political actors. A tone that contrasts with that of some of his followers on that same election night, much more in favor of a confrontation in different fields.

Undoubtedly, the new president is going to move on a tortuous path full of pressures that, if maximized, may end up jeopardizing the stability of his government. But, listening to his first speech, it seems that the president-elect is aware of this. It will be necessary to see if his closing sentence is true: “Costa Rica, the best is yet to come!” Especially considering that a significant part of the country thinks the opposite.

Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva