The approval of indefinite re-election in El Salvador, which paves the way for President Nayib Bukele to remain in power indefinitely, along with the pantomime through which Nicolás Maduro proclaimed himself the winner in Venezuela’s recent elections, brings us face-to-face with the true nature of political regimes in the region. Are they democracies? If democracy means more than merely casting a vote from time to time, then the answer is no.

Are they “fatigued democracies,” as some now label these regimes? But wait—fatigued from pursuing what, exactly? Fatigue arises after sustained effort, which usually results in some achievement but leaves the actor exhausted. To describe our political regimes as “fatigued” suggests, perhaps unintentionally, that at some point these “democracies” (quotation marks very much intended) were genuine democratic regimes that have simply lost steam in continuing their development. But is that really the case?

If we subject the experiences endured across the region to relatively simple tests, serious doubts arise. Let’s begin with the balance of power among branches of government. In how many countries has the judiciary truly acted as a counterweight to the executive and legislative branches? This may have been the case in Costa Rica in another era, but it’s no longer so clear. Not even in Uruguay, a country often praised for its democratic tradition while forgetting its dark dictatorial period from 1973 to 1985, have judges consistently lived up to their role.

Consider a higher-order principle: equality of rights, an unquestionable pillar of democratic society. What level of equal rights has been achieved by citizens across Latin America? If we look beyond the empty promises of constitutions and deceitful legislation and turn to reality, equality of rights remains a distant goal in nearly every country in the region. Poverty, rudimentary education systems, and other massive barriers prevent citizens from exercising their rights on equal footing.

In those countries where some progress has been made toward this goal, it often came thanks to governments that we would hesitate to call democratic. Take two examples. In Argentina, Juan Domingo Perón fostered a degree of social equality by empowering labor unions, which he, of course, co-opted and brought under political control. In Peru, a government born out of a military coup and subsequent electoral fraud—Manuel Odría’s regime—introduced women’s suffrage and established public social security.

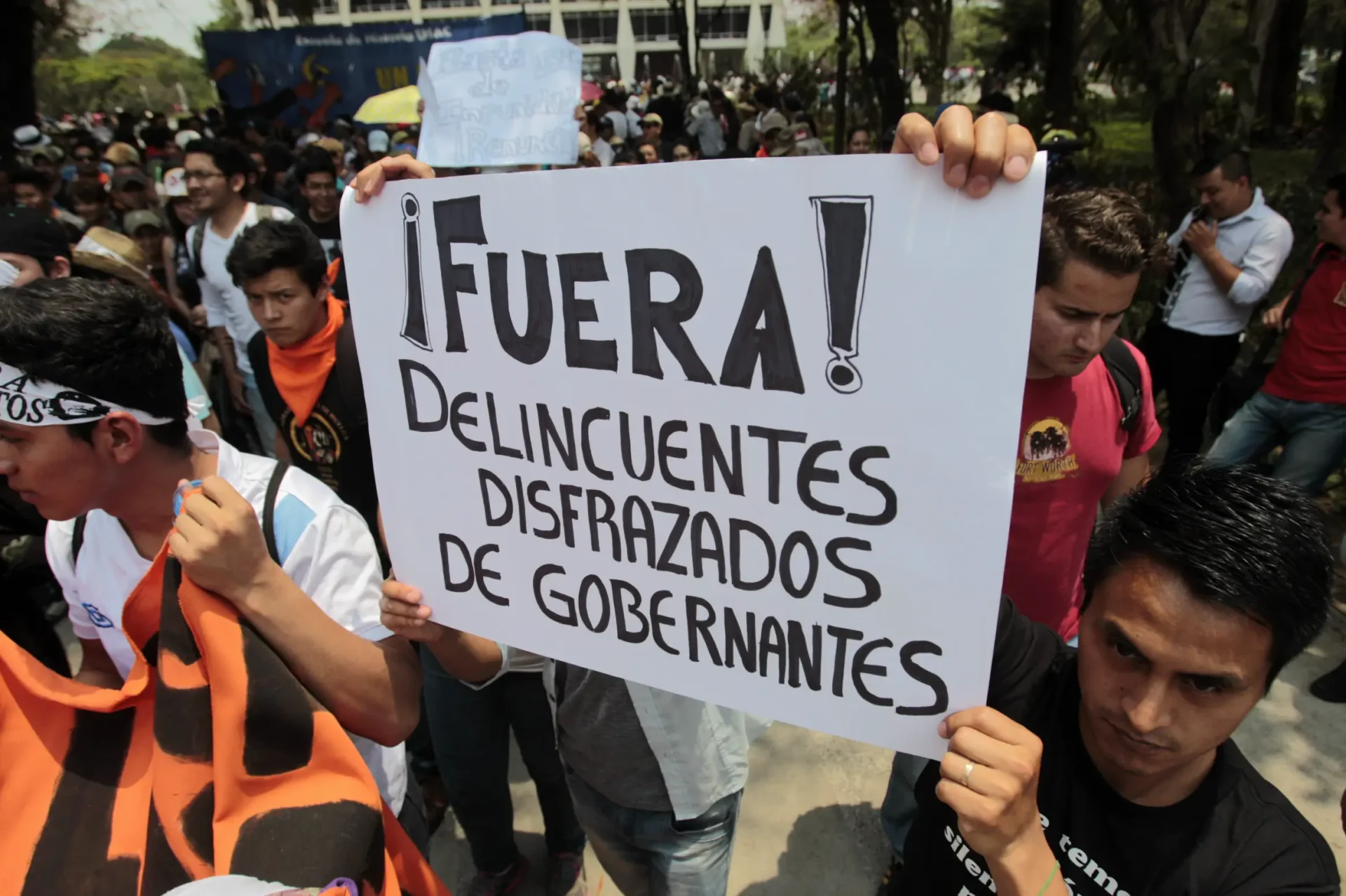

If what we’ve had in the region can hardly be called more than regimes that occasionally allowed voting, why then insist on labeling them “fatigued democracies”? The more compelling trend reflected in repeated surveys is the rise of fatigued citizens—men and women disillusioned by the “democracy” they live under, one that merely lets them periodically choose who will next betray their expectations.

Out of this collective weariness, perverted democracies have emerged and spread. These regimes retain voting processes and respond to some broad social demands while simultaneously working—through good or bad governance—to eliminate any opposition. The rise in crime and insecurity has given oxygen to proposals like Bukele’s, which, in exchange for cracking down on gang violence, is dismantling the basic rights of Salvadoran citizens.

The cases of Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela show just how far democratic perversion can go. So far, in fact, that no one in good faith could still call these systems democracies. Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, know no limits. They don’t even bother with appearances, jailing anyone who dares to oppose them without even trying to disguise it. Maduro clings to power by any means necessary, at the cost of millions of Venezuelans who have fled the country not only for political reasons but, above all, for economic survival. And when it comes to Cuba, this somber review doesn’t even need to go there.

Ultimately, even in these most extreme examples of degeneration, the origin is not “fatigued democracy” but rather failed democracy—regimes incapable of delivering meaningful results for their citizens. That’s why, alongside mounting dissatisfaction, surveys now reveal a sharp decline in people’s faith in democracy. That’s the landscape we face.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves.