The recent Ecuadorian elections have been some of the most outrageous in the country’s recent history. The fragmentation of the vote and institutional distrust, present today more than ever, act as an obstacle to governability. However, on top of this, the incompetence of the National Electoral Council and the rise of the indigenous movement are two of the most characteristic features of the electoral process. In this context, Quo Vadis, Ecuador?

Since the calling of the elections, disputes between the National Electoral Council (CNE), the body in charge of organizing the process, and the Electoral Contentious Tribunal (TCE), responsible for resolving electoral disputes, caused delays in the confirmation of the political organizations authorized to compete in the last general elections on February 7th. The two parties that faced more problems for their approval were “Centro Democrático” (CD), headed by Andres Arauz and supported by former president Rafael Correa” and the “Movimiento Justicia Social,” of the perennial candidate, Alvaro Noboa Portón. While the former managed to present its candidates, Noboa’s party was left out of the race, but its process before the TCE will continue.

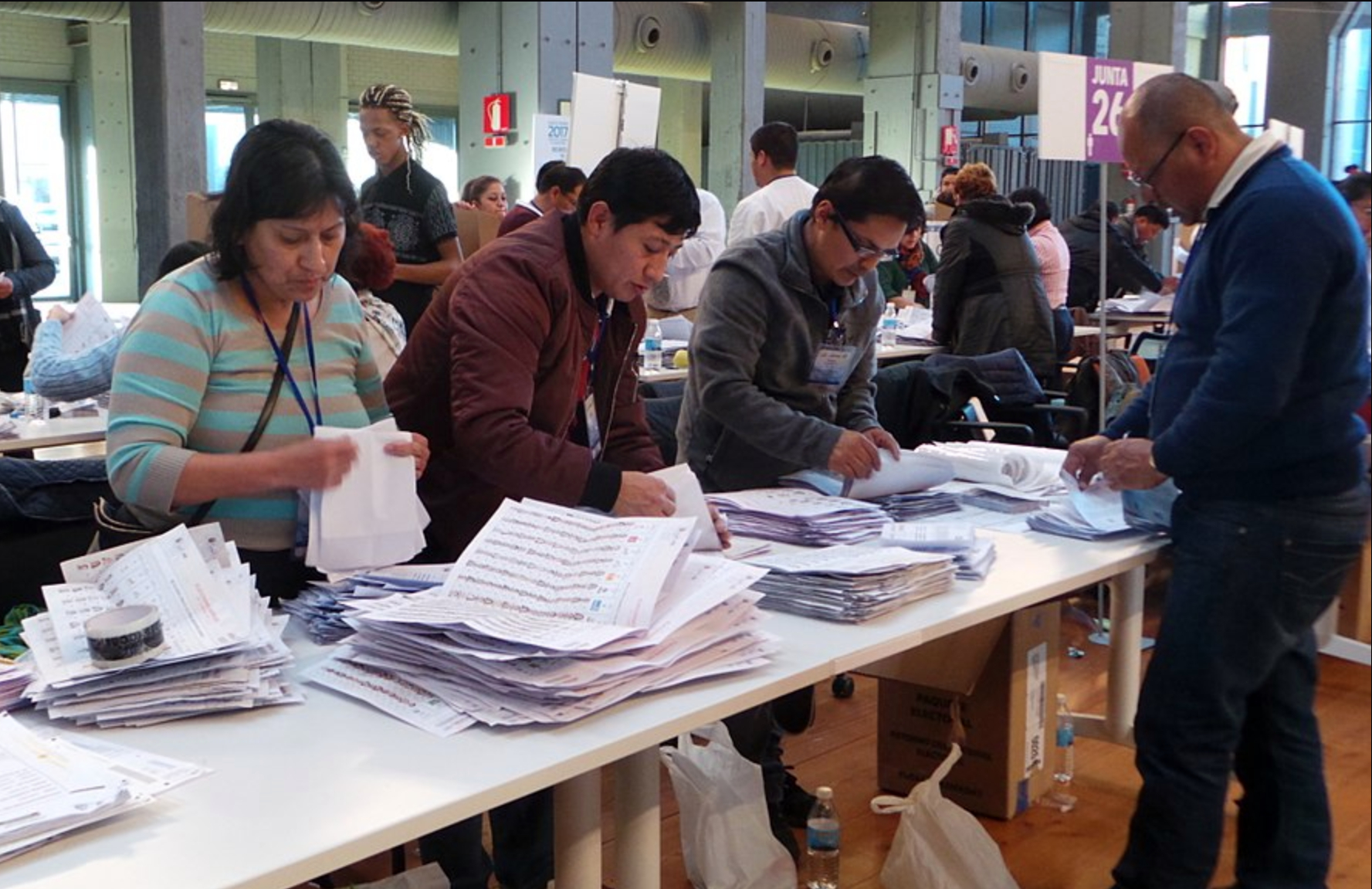

However, this has not been the only controversy. At the beginning of January, and with about 40% of the ballots for the election of President and Vice President printed, a mutual error was found, since both the name and logo of the “Movimiento Amigo” had errors. This resulted in an economic loss of $500,000 USD to the State, in addition to numerous criticisms for its inefficiency. Likewise, at the beginning of the election day there were a few glitches, such as the absence of the members of the polling stations (JRV), the delay in their installation and long lines to enter the electoral precincts.

The rise of the indigenous movement

Despite the obstacles and difficulties, further aggravated in the context of the pandemic, the elections took place on February 7th. That same night, after a quick count carried out by the CNE, it was announced that the coalition, “Union for Hope,” led by Arauz, had obtained 31% of the total valid votes. The surprise came with the second most supported candidate, Yaku Perez of Pachakutik, who had 20.04% of the votes. In third place, with 19.97% of the votes was Guillermo Lasso, head of the CREO Movement. However, with the advance of scrutiny, Perez dropped to third place and with only a difference of 20,000 votes, Lasso went to the second round.

The possibility of Yaku Perez reaching the second round generated a lot of expectations due to the possibility of having an indigenous president for the first time. For this reason, when the scrutiny progressed and Lasso overtook the leader of Pachakutik, some voices expressed doubts about the reliability of the process. This distrust towards the results is not something new: already in 2017, in the runoff between the same Guillermo Lasso and Lenin Moreno, claims were made against the first candidate for alleged fraud. However, the matter did not go further due to the absence of evidence.

Institutional distrust and fault lines

Ecuador is a country whose democratic institutions have not traditionally enjoyed high levels of credibility. Therefore, if the continuous logistical and communication errors that have accompanied the current electoral process are added to this structural distrust, it would not be strange that, with regards to the April 11 runoff election, doubts about the outcome of the elections would increase. This would not only affect the perception of the citizens towards the institutions, but would also put the next president of the Republic in a delicate situation.

Together with the increase of distrust, the results reflect three other dynamics evident in current Ecuadorian politics: the persistence of regional differences, a deep crisis along the center-to-right spectrum, and that the “unbeatability” of Correism has disappeared. The regional cleavage is evident in the distribution of votes among the candidates: while Arauz has concentrated most of his votes in the coast, where he has obtained an average of 42.94% of the votes, in the highlands region, Yaku Perez has been the winner in most of the provinces. Thus, despite the fact that the correísmo-anticorreísmo axis persists in political actors’ discourse, in practice, the distribution of the vote responds to regional differences to a greater extent.

Regarding the crisis in the right and center-right parties, after 8 years of campaigning and three consecutive elections, Lasso has not been able to consolidate his conservative proposal as the great political alternative to the ruling party. If one compares the results of the 2017 elections, where he obtained 28% of votes in the first round, in just five years, he has lost almost 10% of his electorate. The results of the legislative elections reinforce the crisis of the conservative forces. Of the 137 seats, only 23.33% will be composed by legislators of this trend (CREO Movement, Social Christian Party, United Ecuador Movement and Construye).

Finally, Correism is no longer an unbeatable force. Its candidate, Andres Arauz, has obtained about 7% less support than his predecessor despite the continued presence of Correa in his campaign. Despite expectations of winning in the first round, a runoff will be necessary. Furthermore, in the case of winning in the second round, it will be a minority government since it has not been able to obtain the 69 deputies necessary for parliamentary control.

Fragmentation and disenchantment

These elections, in addition to the shadows generated by the dismal performance of the National Electoral Council, are characterized by leaving a political scenario different from the one Ecuador has had in the last decade. On the one hand, the fractioning of the vote is clear. On the other hand, the emergence of the indigenous movement as a solid electoral option that not only has options in the provinces with the largest indigenous population (Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, Tungurahua, Cañar), but also triumphs in the popular urban centers (for example, in the south center of Quito or in the province of Azuay) stands out.

The right or center-right voter has little reason to hope. Since 1998, no party of this movement has won a presidential election. Correa supporters have reasons to worry. Former president Correa is no longer the president of yore and the candidates of his movement are not always the winning option. Arauz will have to compete in the second round knowing that his critics will try to energize the vote in favor of any other option to prevent the former president and his long shadow from returning to the country.

In the midst of the most intense elections in the last 20 years, with the distribution of power among four political forces in the legislative branch, which will generate a very weak government, and under a shadow of institutional distrust, Quo Vadis, Ecuador?

*Translation from Spanish by Marika Olijar

Photo by Montserrat Boix