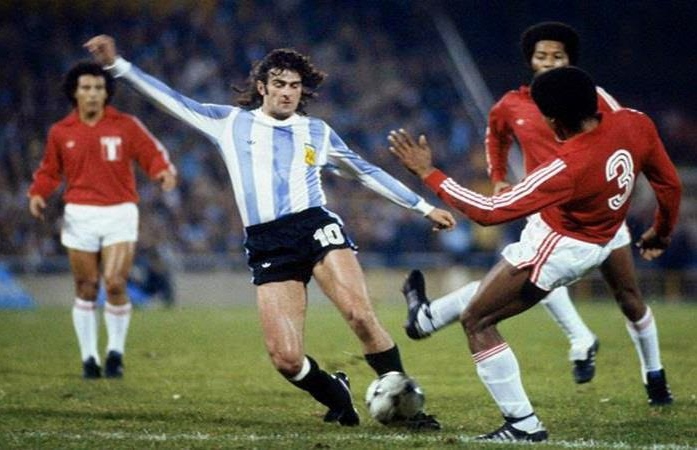

On June 21, 1978, at the Gigante de Arroyito stadium in Rosario, Argentina, the national teams of Argentina and Peru played one of the most controversial matches in the history of the continent’s soccer. It was the last match before the 1978 World Cup final in Argentina. The Netherlands had already qualified for the final and were waiting for their opponent to be decided: Brazil or Argentina.

On the same day, Brazil had defeated Poland 3-1, shortly before the match between Argentina and Peru. The tempos of the match were suddenly reversed, so the hosts went into the match knowing that a four-goal win would qualify Argentina for the final. Otherwise, Brazil would play the Dutch for the title. In front of 40,000 fans, Argentina thrashed Peru 6-0 to qualify for the final. They then defeated the Netherlands 3-1 to win their first World Cup title.

The political context in Argentina during the World Cup was one of military dictatorship. From 1976 to 1981, the country was ruled by General Jorge Rafael Videla, who took office after the deposition of Isabelita Perón. For some historians, ’78 was the high point of the military regime, less for the government’s successes and more for the nationalist triumphs in international competitions.

Argentine tennis player Guillermo Vilas was at the peak of his career with three Grand Slam titles in 1977-1978 (Roland Garros, US Open and Australia Open). Model Silvana Suárez would be elected Miss World at the end of that year. And, with greater popular appeal, the national soccer team would win the World Cup, which was used as political propaganda and to boost the country’s international image.

At the same time, the delirium provided by the international competitions increased the reports of assassinations, torture, political imprisonment, exile and forced disappearances. In the economy, deindustrialization, unemployment and the inflationary spiral increased. This other side of the coin did not prevent part of the population from applauding General Videla at the Monumental de Núñez stadium, where Argentina was champion, and at the Plaza de Mayo, during the celebration. A pernicious combination of soccer, politics and nationalism.

As for the controversial 6-0 victory, there has been much speculation about the physical condition of Peruvian goalkeeper Ramón Quiroga (“El Loco”). In addition to conceding six goals, Quiroga is a naturalized Peruvian citizen of Argentina, which has led to suspicions of an alleged bribe to concede the match, an accusation he has always denied. In fact, an analysis of the goals shows that Quiroga does not appear to have been guilty of any of them, in contrast to two or three clear mistakes by the Peruvian linesmen. In a report published by Folha de Sao Paulo in 1998, Quiroga claimed that he was sure that someone had made money to give the game away.

In 2005, journalist Pablo Llonto published the book “La vergüenza de todos” (The shame of all), with an analysis of the rumors of that cup. The author argued that the Argentine team won the game on the field, without outside interference, despite the speculations that persist to this day. In 2007, Colombian radio station Caracol announced that the Cali cartel had bribed some players of the Peruvian national team. The claims were made by Fernando Mondragon, son of Gilberto Orejuela (“El Ajedrecista”), a former Colombian drug lord.

Also in 2007, the documentary “Mundial 78: Verdad o Mentira” (World Cup 78: Truth or Lie), directed by Christian Rémoli, was released. The director showed that shortly before the start of the match between Argentina and Peru, General Videla and former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger went to the Peruvian team’s locker room to talk about solidarity and Latin American unity, which was interpreted by some players as an act of political pressure.

There was also speculation that the Peruvian government would donate thousands of tons of wheat to the team after the defeat. In 2008, Ricardo Gotta published “Fuimos campeones: la dictadura, el Mundial 78 y el misterio del 6 a 0 a Perú”, which addresses these and other speculations, with evidence pointing to the existence of bribes on and off the field.

It is recalled that in 1978 Peru was governed by General Francisco Morales Bermudez, then head of the self-proclaimed “revolutionary government of the Armed Forces” of Peru. In itself, it was a troubled period in the country’s history. In 2012, former Peruvian senator Genaro Ledesma (1931-2018) charged that the 6-0 thrashing would have been part of an agreement between the military governments of the two countries, and would also include financial aid and political cooperation. Nothing has been proven.

In 2018, in an interview for the Peruvian newspaper Trome, former player José Velásquez (“El Patrón”) claimed that six Peruvian players gave away the game, citing names. But it was not clear which “surrender” he was referring to. It was also reported that Brazilian team officials offered money to the Peruvian team not to lose the game by more than three goals (the famous “white bag”), which would take Brazil to the cup final. It is easy to conclude that the Brazilian proposal was not accepted by the Peruvians.

Another possibility that cannot be ruled out is that the Argentine team played one of its best games in the history of World Cup participation, having won the match on the field without external interference. In that case, Videla and Kissinger’s visit to the Peruvian dressing room would have been a mere goodwill visit. This hypothesis is reinforced by Argentina’s convincing victory in the final against the Netherlands.

In short, there is much speculation. But there is no evidence, only personal testimonies. I believe that all of the above hypotheses are plausible.

To conclude, it is worth reflecting briefly on the relationship between politics and soccer in South America, where soccer is an instrument historically used by rulers to promote their image and gain popular prestige.

In 1970, Brazil’s World Cup title in Mexico had a very similar impact to Argentina’s title in 1978. In both cases, governments took advantage of soccer to revitalize their political legitimacy and disguise economic weaknesses.

Argentina, now redemocratized, again made political use of soccer when it won the 1986 World Cup, also in Mexico, revitalizing the country’s image, eroded by its defeat in the 1982 Falklands War. Maradona’s goal (1960-2020) against England, popularized as “The Hand of God,” is considered by many to have been a kind of capitulation by the English, the result of an allegorical association between politics and soccer.

Much of the history of the relationship between politics and soccer is the result of the testimonies – oral history – of those who participated in the events. In this logic, time is a fundamental variable to take into account. As the years go by, the characters of history cease to exist and, therefore, the natural phenomenon of the “burning of archives” takes place.

There are countless debates that enter into the orbit of speculation and desire, far from the reality of the facts. In this field full of uncertainties, it is plausible to admit that soccer -in South America and in other regions- is susceptible to be instrumentalized in favor of populism, diverting the population’s attention from its real challenges.

*Translation from Spanish by Ricardo Aceves