According to the most recent estimate, in 2020 there were approximately 281 million migrants in the world, a figure equivalent to 3.6% of the world’s population. In the case of Latin America, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) indicated that almost 18 million people (around the population of Ecuador) live outside their home countries. The growing migratory flows have made it necessary to rethink the constitutional and legal frameworks for political participation.

Some countries with a more established migratory tradition, such as Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador, have been adapting their laws to guarantee the rights of their citizens abroad (they even have deputies who represent their residents outside the country). However, there are still other countries that do not establish (for the members of their diasporas) the exercise of voting from abroad or the possibility of running for elected office.

At present, 17 countries in the region guarantee the vote of their citizens abroad: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Per, and Venezuela. Uruguay, Suriname, and Cuba have not yet made progress in this type of legislation.

In the case of Uruguay, a bill was introduced earlier this year to allow the nearly 600,000 residents out of the country, equivalent to 17% of the population, to exercise their political rights by voting from abroad.

As for Cuba, the National Assembly, in which only the Communist Party (PCC) is represented, has not made any progress in the recognition of the political rights of the diaspora, on the understanding that the millions of Cubans abroad are opponents. In fact, the only persons authorized to vote outside Cuba are diplomatic representatives and members of medical, sports, or educational missions, all of them dependent on the Government.

But it is not enough to guarantee migrants the right of voting from abroad. It is also necessary to establish mechanisms to facilitate the registration or updating of voters, as well as the casting of ballots.

Venezuela, for example, provides for the vote of residents abroad but systematically prevents them from registering or updating their addresses. Thus, with more than 7 million Venezuelans abroad, only 107,000 are registered.

In other cases, we find that the vote abroad can only be exercised in diplomatic or consular offices, but these are insufficient for the totality of potential voters. A trip of hundreds of kilometers discourages even the most committed citizens.

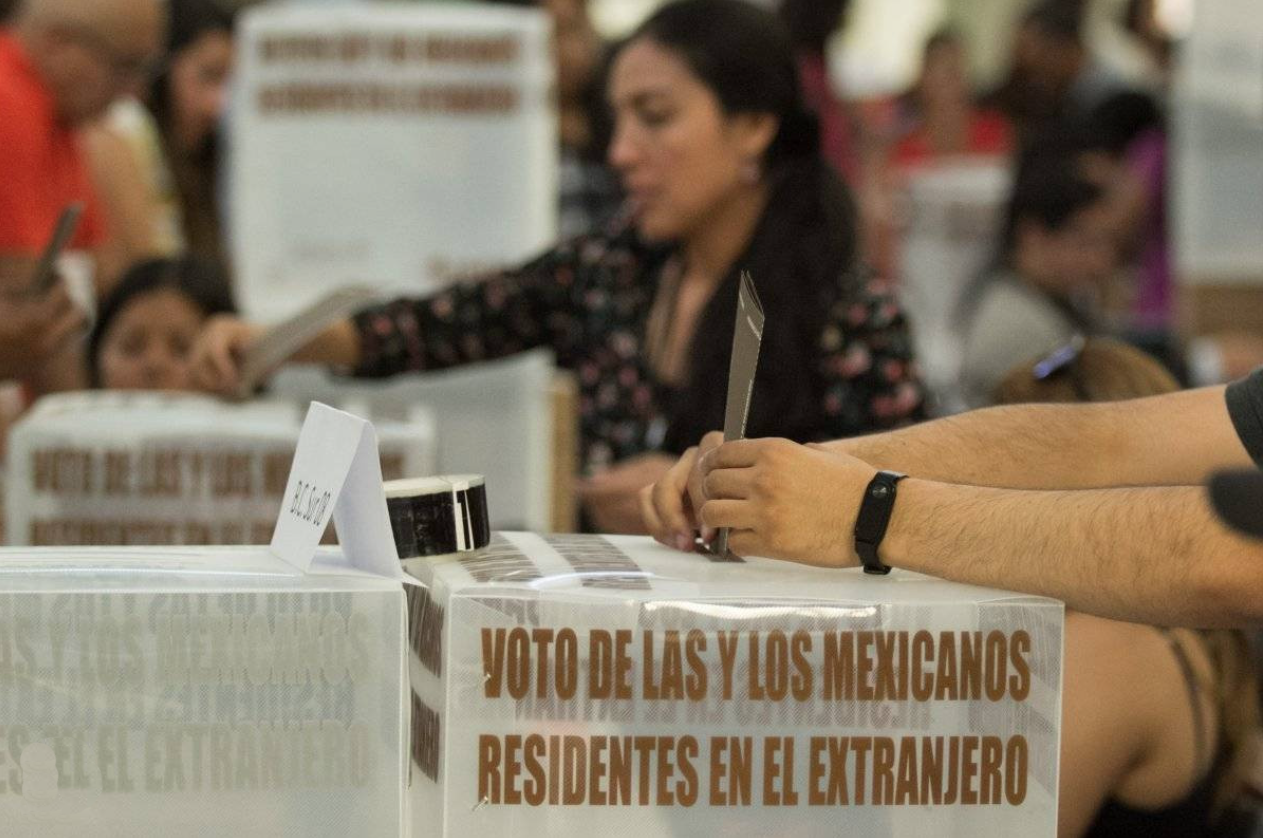

Thus, electoral bodies must be innovative and create solutions that facilitate the political participation of the diaspora. This is the case of Mexico, which for the elections in the States of Mexico and Coahuila last June 4, made available three modalities for its residents abroad to cast their vote.

For the first time, thanks to an agreement between the National Electoral Institute (INE) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (SRE), Mexicans could vote in consulates and embassies in the United States (Dallas, Chicago, and Los Angeles) and Canada (Montreal), send their vote by mail or do it remotely over the Internet through their phone, computer or tablet.

Almost 8,000 people were eligible to vote abroad in these two districts: 5,424 from the State of Mexico and 2,350 from the State of Coahuila. Taking into account that in last year’s recall referendum, which was nationwide, 17,000 people registered, it was not a small number.

The number of registrants that chose to vote online was 4,804. Many of these people found remote voting an opportunity to participate in the political affairs of their home country without the need to move from their workplaces or their homes. Finally, 40% of the people who registered in this modality cast their vote via Internet, a good omen, thinking about next year’s elections, which, due to the number of candidates to be elected, will be the largest in the history of the country.

Fortunately, we cannot say that this is an isolated effort in Mexico. Democratic institutions, both at the national and subnational levels, have made a commitment to innovate in order to promote political participation. Different subnational electoral bodies, such as those of Jalisco, Coahuila, or Mexico City, have developed their own technological tools for voting. The INE, for its part, has been a pioneer in the use of technologies for the transmission of data, and provisional counting, and in this case, it is moving forward together with local bodies to facilitate the participation of residents abroad.

There are still many challenges for the rights of migrants to be guaranteed, but we can say that this effort by Mexico’s electoral authorities is going in the right direction.

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva