Political scientist Adam Przeworski delivered a lecture this October at El Colegio de México in which he analyzed the challenges and limitations of political science in addressing democratic backsliding. In one of his slides, he recalled that during Spain’s Transition, Adolfo Suárez declared: “The future is not written, because only the people can write it.”

However, immediately after this quote, Przeworski wrote: “And the people can write dangerous things.” The authoritarianisms of the 21st century have become so sophisticated that they no longer need the military to seize power. They play under the same rules of democracy, and when they win elections, they blow it up from within. Now autocrats seduce the population with speeches, promises, and the argument of a better future.

Presidential regimes such as those of the United States, Mexico, El Salvador, and Brazil have witnessed the rise of authoritarian figures sheltered by broad majorities. Authoritarians dress like democrats and mobilize wills that provide them with a shield against criticism for co-opting institutions and concentrating power. Guillermo O’Donnell referred to this as delegative democracy.

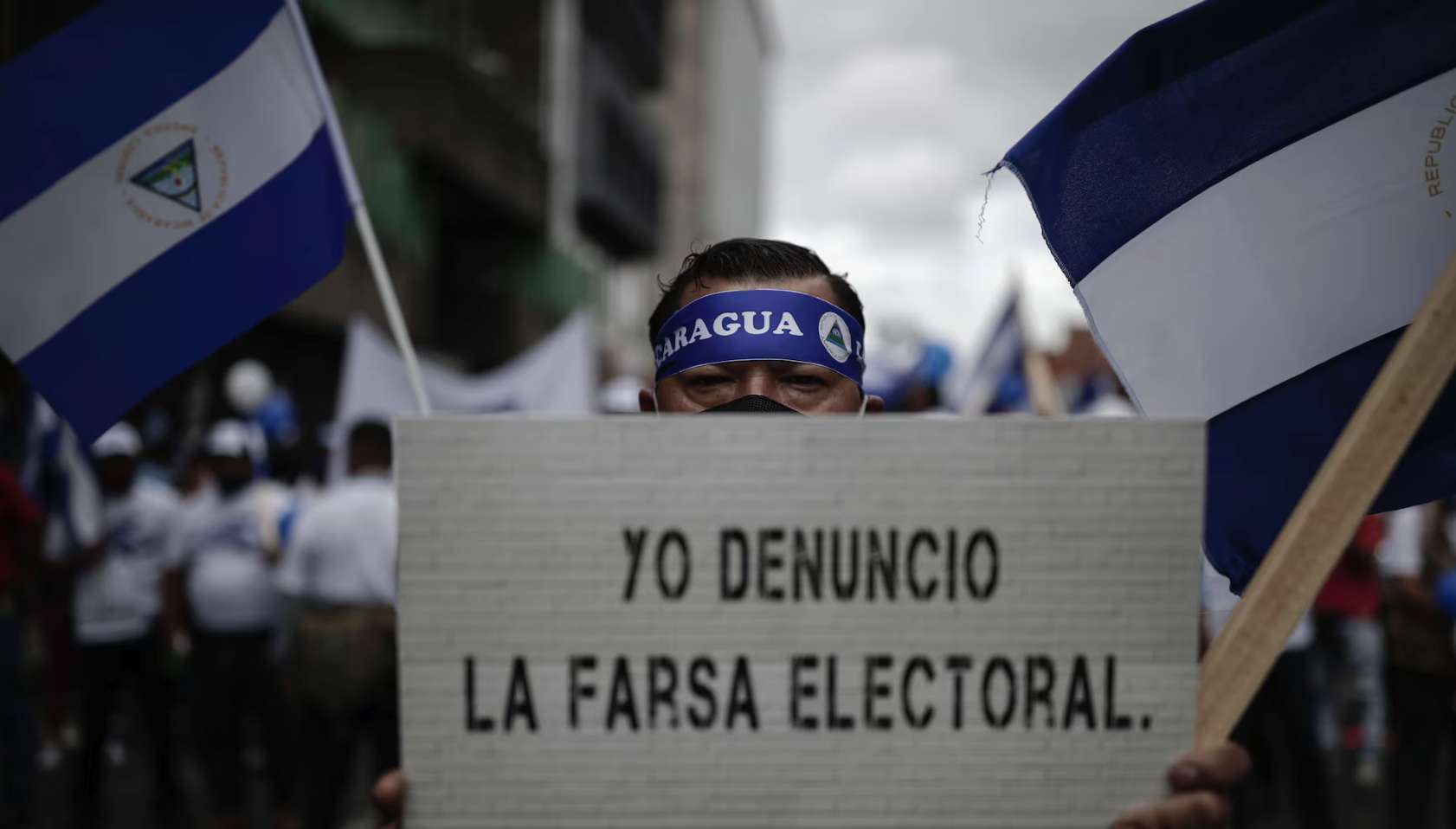

Democracy in its minimalist definition is characterized by the holding of periodic elections. Over time, it has become evident that not all types of elections are democratic; however, the participation of citizens stands out as a determining factor for a party or figure to gain power. The course of nations is written by their voters, but according to Przeworski, they can also choose dangerous paths.

At first, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela defeated the bipartisan system through the ballot box. He then used it to legitimize constitutional changes and undermine democracy. In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro questioned the electronic voting system when the results were not favorable to him. The outcome was the assault on Brazil’s branches of government, something very similar to what Trump incited in 2021 when his supporters attempted to enter the Capitol.

In the events mentioned previously, there were people willing to defend a person or party with whom they identified. Democracy was not defended as a synonym of plurality but of imposition. Authoritarians and their voters have forged bonds of dependency. The former present themselves as the voice of the majority and the humiliated; the latter fiercely defend their actions, statements, and even aggressions toward other sectors. Both protect each other.

It is important to point out that some branches of political science seek to understand electoral behavior. Initially, it was believed that citizens opted for authoritarian figures because they succumbed to populism; however, the complexity of the scenario has led to the consideration of other elements. The book The Autocratic Voter, by American political scientist and professor Nataly Wenzell Letsa, explores how social media, polarization, and partisan identity influence the political culture of citizens in supporting autocrats.

Another example of authoritarians seducing the population is Bukele’s El Salvador. Nicknamed the “cool dictator,” the population has ceded its political freedoms in exchange for security. In Mexico, Morena and López Obrador promised the democratization of justice, and under that argument imposed judicial elections that ultimately undermined the separation of powers.

However, the story is no different in Europe’s parliamentary systems, where radical right-wing parties compete under the banner of democracy. Sweden Democrats is the nationalist party that forms part of governing coalitions; Austria’s Freedom Party and the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom are characterized by their xenophobia, Euroscepticism, and exacerbated nationalism. These parties reap electoral victories because there are people who support them.

Meanwhile, some prime ministers such as Robert Fico in Slovakia, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, and Andrej Babiš in the Czech Republic have established themselves as the illiberal leaders of their nations. Their electoral success is due to the combination of nationalism, Christianity, and the mobilization of emotions. There is a clear discontent with democracy and its institutions, but citizens are also responsible for their decisions.

From various perspectives, elites who opt for authoritarianism, traditional parties that become hermetic, and inefficient institutions have been questioned. However, the citizenry—just as it is responsible for the decisions it makes and for the protection of democracy—is also responsible for its erosion and for the rise of authoritarianisms. When people choose an option on the ballot, they might be choosing something dangerous.

*Machine translation, proofread by Ricardo Aceves