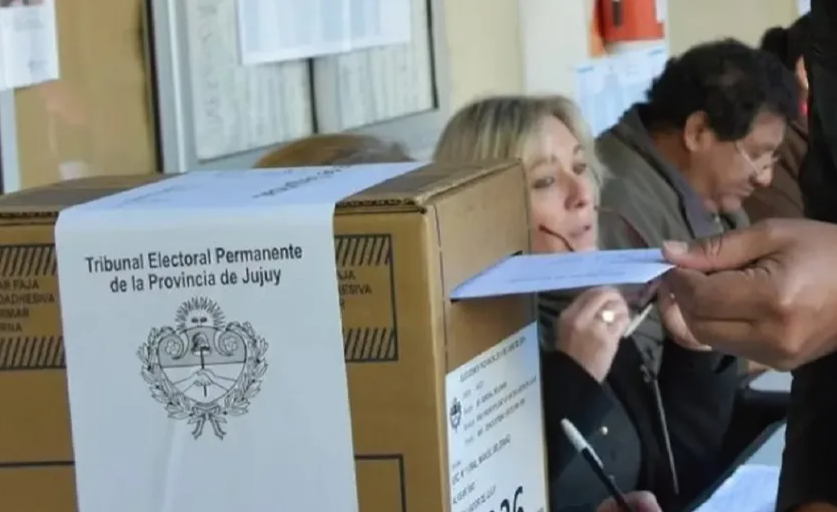

The general elections in Argentina were held on October 22. The general atmosphere was one of tranquility and civility, with no major incidents to lament. The initial results were announced before the scheduled time (10:30 pm), as a clear trend was already evident. Since 2019, when the transmission of telegrams from the voting centers was automated, the uploading has been agile and quite homogeneous.

Most of the analyses were about the defeat (and disappearance?) of Together for Change, the impressive performance of the ruling candidate (adding 3 million votes), and, above all, about the possibility of Javier Milei becoming president.

However, we would like to offer another perspective: that of the integrity of the elections and the ability of citizens to audit them. Although international indexes, such as that of “The Economist’s Intelligence Unit”, classify Argentina as an imperfect democracy, and its national elections are rated positively, there is a whole range of bad practices that are constantly occurring and have become naturalized.

These are especially determinant in subnational elections, where we can find indefinite reelections, the law of slogans, couplings, use of state resources in favor of the ruling party, delivery of merchandise or voter harassment. Each of these tools is part of the toolbox of rigged elections and has been used by the ruling parties to perpetuate themselves in power, either through the same party or the rulers themselves (Formosa) or their relatives (Santiago del Estero, San Luis, Santa Cruz).

At the level of national elections, the legal framework does not foresee slogans or indefinite reelections, although there are legal limitations that affect the ability of citizens to audit the process.

For example, in Argentina, there is no electoral observation (national or international). A much more limited one is provided for, the civic accompaniment, but it does not have the status of law, so there are no guarantees that it will be complied with. For example, Transparencia Electoral tried to accredit a civic accompaniment mission in the PASO and the general elections. On the first occasion, the request was denied by the National Electoral Chamber. In the second, it was not even answered.

As for the electoral competition conditions, a tilted playing field scenario was evidenced, with the ruling party making indiscriminate use of state resources in favor of its candidate, Sergio Massa, who, although he is Minister of Economy, has monopolized the governmental media presence making not only economic announcements but also infrastructure, sports and tourism announcements, acting as a plenipotentiary minister.

This section also includes issues such as the biased coverage of Public Television during the electoral campaign, in which the segments dedicated to the opposition forces Together for Change (JxC) and Liberty Advances (LLA) were mostly negative; the discretion distribution of bonuses for the national public administration and the private sector, bonuses for public employees in some provinces (i.e.: Santiago del Estero), the distribution of handouts and household appliances at a local level, and more recently, the use of public institutions and spaces administered by the national state to carry out proselytizing activities at a national level. e.g.: Santiago del Estero), the distribution of handouts and household appliances at the local level, and, more recently, the use of institutions and public spaces administered by the national state for proselytizing activities, as is the case of the campaign on train ticket subsidies.

The candidate of the ruling coalition — Union for the Fatherland (UxP) —, Sergio Massa, did not depart from his position as Minister of Economy and made use of his attributions and those of other ministries to carry out official acts that qualify as campaign acts. The announcement of the World Cup 2030 in Argentina, in which he accompanied the president of the Argentine soccer federation (AFA) and the Minister of Tourism; the withdrawal of social plans for those who participated in the looting at the end of August, and the announcement of public works, such as the pretreatment plant of the Riachuelo System, stand out.

Due to these issues, together with the weaknesses of the partisan ballot, the handouts, the voter’s harassment, and the lack of measures to guarantee the participation of Argentines living abroad, we can conclude that this was an electoral process with a great margin for improvement.

The political parties and the organized civil society must work to reach a consensus on reforms to the National Electoral Code to strengthen the quality of the elections and improve their integrity and competitiveness.