Using a life-cycle perspective, it is clear what inequities, and how, affect the health of people in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). From the moment we are conceived, where and under what conditions we are conceived define our development in the womb, our birth, our first 1,000 days on the planet and, without exaggeration, much of our future well-being and ailments. To begin with, we depend on the health of our mothers. Sex education and access to contraceptives are limited in the region, while gender-based violence is widespread (child, early and forced marriages and unions impact 1 in 5 girls). As a consequence, we have the second-highest rate of teenage pregnancy in the world. Nineteen percent of all births are to women under 20 years of age, with the health problems that early pregnancy entails for the mother (depression, anemia and obstetric complications) and the baby (low birth weight and other neonatal conditions).

Prenatal care, which accounts for a significant portion of public investment, does not reach all mothers and their children equally in our region. Pregnant women with higher levels of education will attend more prenatal care than women with lower levels of education (none or only primary education). The lowest coverage of prenatal checkups is found in the lowest income countries such as Guatemala (around 60%). In that same country, the maternal mortality ratio is 96 per 100,000 live births when the Sustainable Development Goals target is 70 per 100,000. The risk of maternal death is three times higher in adolescents under 15 years of age than in women over 20 years of age in LAC. At least 10% of all maternal deaths in the region are due to unsafe abortion. This is because abortion is illegal with few exceptions (rape, severe fetal abnormality) in some countries. Even so, more than a third of pregnancies (estimated at 670,000 in adolescents aged 15-19 alone) end in induced abortion annually.

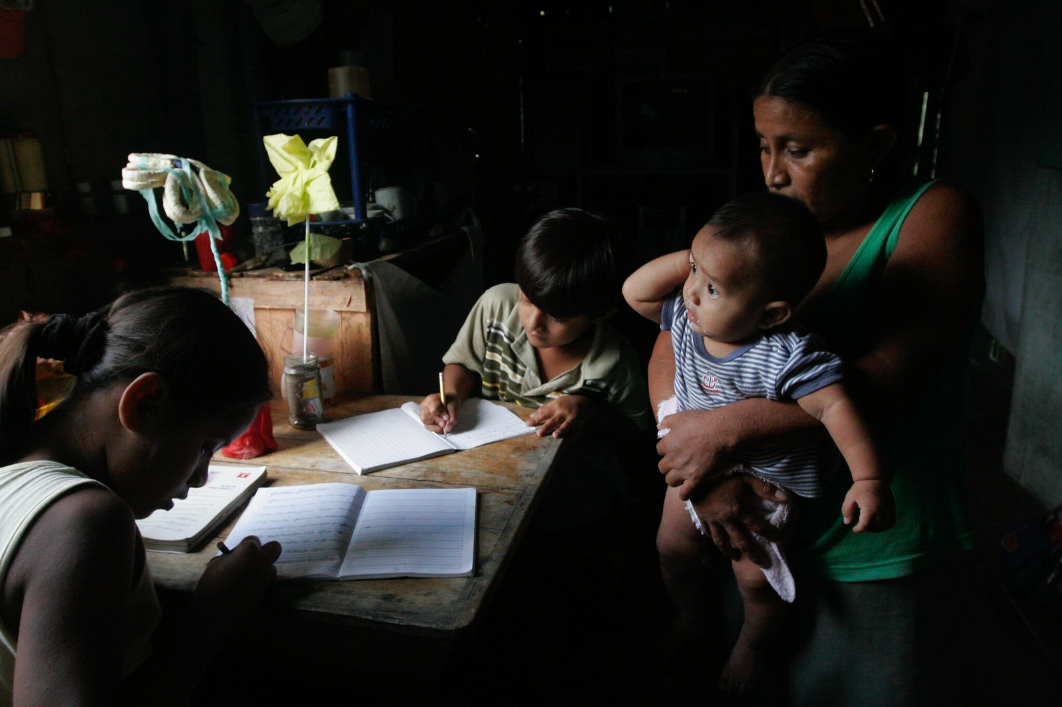

Infant mortality is another clear indicator of health inequities in LAC. From the moment we are born, our survival will be defined by our living conditions. If we crawl on dirt floors, we will be in direct contact with parasites — which cause diarrheal diseases leading to chronic malnutrition and even death (0.51% of all deaths in the region). If we grow up near an illegal mine, we will be exposed to heavy metals such as lead — which leads to anemia. Thus, children under five suffer persistently high malnutrition rates in countries such as Guatemala (43.5% on average) and Ecuador (27.4% in the rural Sierra, where there is a high percentage of indigenous population), as well as high anemia rates (36.9% in Bolivia and 38.2% in Ecuador), where illegal mining is rampant. Accordingly, the average infant mortality rate of 25 per 1,000 in the region is five times the OECD average. The difference in infant mortality between the richest and poorest households in countries such as Paraguay is equally alarming: it is 20 times higher in the first and second quintile of the population than in the richest quintile, where it is close to zero.

Once we have passed the tests imposed in the early stages of our lives, we will reach adolescence, where the initial cycle will repeat more rapidly in the most disadvantaged sectors. At the onset of adulthood, the inhabitants of LAC will be actively confronted with poor nutrition and its impacts. Food insecurity is more prevalent in the region (14.2%) than in the world (11.7%). This implied that 56.5 million people were suffering from hunger in 2021. Concomitantly, 22.5% of the population cannot access a healthy diet, which is influenced by the country’s income level, the incidence of poverty and the level of inequality. In the Caribbean, the proportion reaches 52%, in Mesoamerica, 27.8% and in South America, 18.4%. Diet quality is linked to overweight and obesity, which in turn are related to the risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In the region, obesity affects 24.2% of adults, well above the estimated world average of 13.1%. In the Bahamas, it exceeds 30%, while in Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominica, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Suriname, and Uruguay it affects one in four people.

The environment in which children are conceived and raised is the same as those of adults, and in areas and homes with fewer resources, they will be exposed, for example, to greater pollution. In the region, indoor air pollution in homes causes the death of 15 people per 100,000 annually. In countries such as Haiti, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay, Nicaragua and Bolivia, mortality rates from this cause are two to four times higher than average because traditional stoves and solid fuels are still used. The most vulnerable populations, such as women, indigenous people and the poorest, suffer the most health impacts.

In the end, our life expectancy will also depend on our socio-environmental conditions. The level of education, access to safe water and sanitation, and overcrowding make a major difference in cities. Panama, Chile, and Costa Rica have the cities with the highest life expectancy (81–82 years for women and 75–77 years for men). While Mexico, Brazil, and Peru have the cities with the lowest life expectancy in women (77–78 years on average). Together with El Salvador, Mexico, and Brazil also have the lowest life expectancy in men (71 years on average).

In short, health inequities in Latin America and the Caribbean are evident from conception, with factors such as limited access to health resources, which disproportionately affects countries with lower than average incomes and vulnerable populations. The limited public spending on health (3% of GDP on average) requires the population to spend a high amount out-of-pocket — twice the public expenditure — in order to have minimum access to services. The impacts extend throughout the life cycle. As people grow older, and into their later years, they face the limits of national economic conditions, environmental controls and their own economic income, but above all the extreme inequities in each country.

*Translated by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva from the original in Spanish.