Latin American political actors have resisted being classified in the categories of left and right, as old as the French Revolution. What has Peronism been if not a challenge to political scientists? In these days, Peru offers an example of a case not easily comprehensible to outsiders, which has put Peruvians in the situation of living in uncertainty because of a government with no direction.

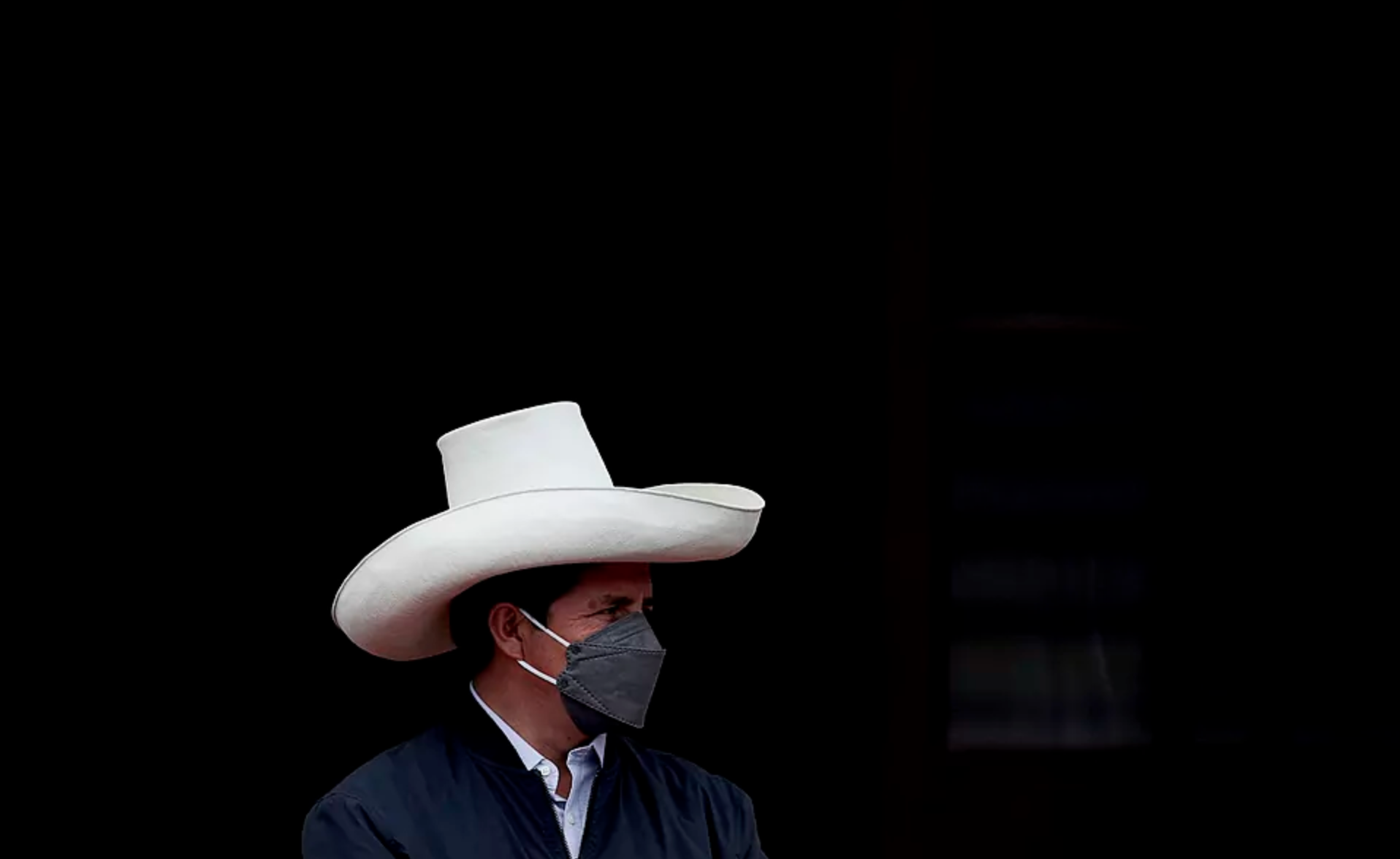

Pedro Castillo was elected in 2021 and was installed in the presidential chair a year ago. He was considered as a leftist figure, who had (and still seems to have) the support of the leftist parties. Among them, that of Perú Libre, the organization that took him as presidential candidate and that responds to the helm of Vladimir Cerrón, the neurosurgeon who lived more than a decade in Cuba and brought to Peru not only the cult of “socialism”, but also a government program in line with it. A judicial sentence for corruption prevented him from being a candidate in 2021.

Last year, Castillo wrote on his Twitter account: “We will continue to fight tirelessly for the changes that the people need. We are the government that drives the social vindication and that bets on the development of our regions. With unity and consensus, we will do it”. Well, what has this government done during this year for the benefit of the people? Little to nothing.

Today, Castillo’s main objective is to survive, a difficult task given that there are six open investigations against him by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In turn, the day-to-day affairs seem to be the only important thing. In the meantime, the Government moves like a decapitated bird: it has just sworn in its fifth ministerial cabinet so far this term and has appointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs an internationalist known for their reactionary positions.

Perhaps the appointment is an attempt to placate the neoconservative sectors (which control a little more than a third of the Parliament) that have made Castillo uncomfortable in his efforts for survival. They have tried twice to remove him from office without the constitutionally required votes. During Castillo’s Presidency (and even before he took office), certain actors and opposition groups have insisted on raising the threat of electoral fraud, even though they have not been able to show any proof.

A “Leftism” devoid of substance

Apart from routinely invoking “the people” in his speeches, Castillo’s time in office has not benefitted the country’s majorities with concrete measures. What has instead been in the news during these twelve months are the various revelations of “irregularities” in matters handled from the Government Palace, some of which have given rise to official investigations. Reports on corruption in public management have filled the written and televised press.

The apparent original form of leftism and its promises have existed, therefore, in a vacuum. And the polls reveal that real people perceive it this way, since, according to the surveys, the President has the support of around one out of five Peruvians. In one year, Castillo has lost more than half of the electorate that elected him as President.

The other context where Leftism is put to the test is in the Parliament. There, Peru Libre, the party that was considered pro-government and was installed in Congress with 37 seats, has lost 21 of them because it split in two. One part of it has remained with Cerrón, and another has formed the so-called “Bloque Magisterial,” which is closer to the President. However, what is striking is that in several important decisions, both groups have coincided in voting preference with the parliamentary sector identified as right-wing. There are a handful of parties that belong to this bloc: the Fujimorists of Fuerza Popular, the chameleon-like Avanza País, and Renovación Popular, whose leader, Rafael López Aliaga, is a well-known militant of Opus Dei who prides himself on wearing the cilice.

Of the various votes in the Peruvian Congress where the Left and the Right have coincided, two stand out. One was the appointment of the members of the Constitutional Tribunal, which this year was negotiated by means of the age-old system of “you appoint yours and I appoint mine,” while ignoring the actual merits and capacities of the candidates.

The other was the dismantling of the quality control system of universities (Sunedu), which had, in a few years, managed to put out of business a series of institutions that called themselves “universities,” but whose sole purpose was profit. They operated with no other objective than to grant unsupported professional degrees. These fake universities have their parliamentary representation, which has been responsible for destroying the quality control system with the help of both the Left and Right. Parliamentary decisions reveal, then, that ideological preferences do not seem always to count in them or are different from those that have been solely attributed to the Left.

A reactionary Left

Strictly speaking, the “leftist” parliamentarians adhere to what has been called the illiberal Left. In the Peruvian case, the Left is reactionary. Covering themselves with the cloak of the Left, they use their seats in Congress to defend particular interests. These interests are no strangers to various “irregular activities.” It is in this definition of their task where no difference can be found between them and the majority of their counterparts in other parties. Both parties are mostly activists of a retrograde conservatism that opposes sex education in schools, abhor same-sex marriage, and downplay the importance of gender violence in a country with growing numbers.

Likewise, the Left and the Right coincide in opposing the demanded early general elections (raised through the slogan “let them all go”) that would deprive the current congressmen not only of their salaries for the next four years, but also of the business under the table that they carry out from their positions.

The Peru of today is in a critical situation whose next stages are inconceivable. But, to try to understand this situation, it is not useful to label the actors as left or right-wing. Lack of preparation, short-sightedness, eagerness to obtain personal or group benefits, disinterest for what in other times was known as the general interest… all characterize those who, with one party or another, agree to take the country in an unknown direction.

Translated from Spanish by Alek Langford