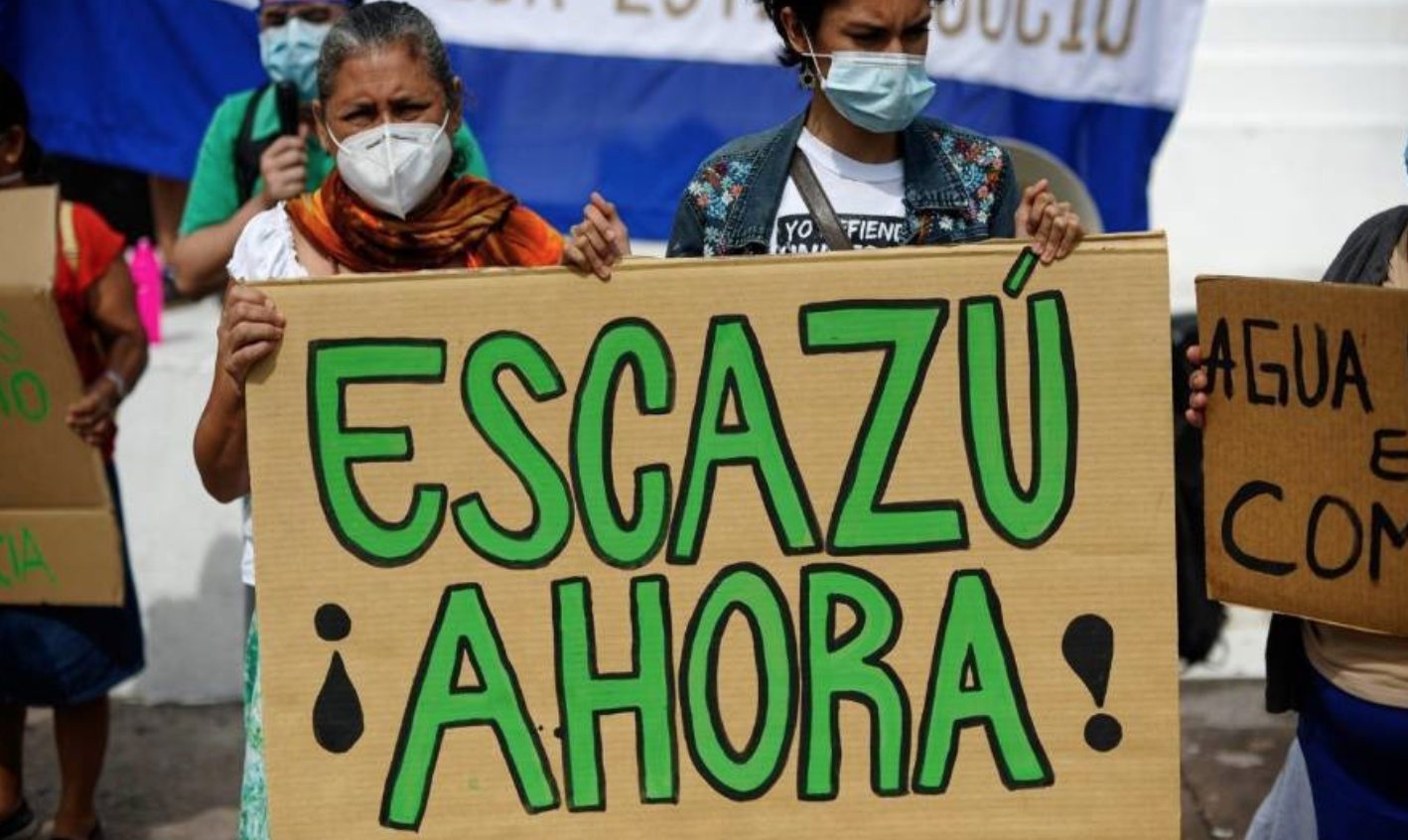

Recently, environmental and human rights NGOs in the region have been calling on their governments to sign up for the Escazú Agreement. Undoubtedly, many are calling for it with full conviction of the agreement’s benefits. However, some voices consider that this is a mechanism conceived by transnational powers to limit the region’s autonomy.

What the agreement is about

The Escazú Agreement is an international treaty on human rights, and territorial and environmental management, subject to the final decision of international tribunals. It applies exclusively to countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and “no other region in the world has signed an agreement of this nature,” explains Venezuelan engineer Julio César Centeno.

According to the Secretary General of the United Nations, António Guterres, the Escazú Agreement “is the only legally binding agreement derived from the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20); it is a historic agreement”.

The agreement is based on three concepts outlined in Principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. This was issued by the NGO summit held in parallel to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, which approved the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Framework Agreement on Climate Change. Basically, the agreement covers public law in three fundamental areas: access to environmental information, participation in environmental decision-making processes, and access to justice in matters affecting the environment.

Thus, the legally binding Escazú Agreement obliges states to disclose, without restriction, all the information they possess about the environment and the country’s natural resources, “including information related to environmental risks, real or potential, and information related to environmental protection and management,” said Centeno.

Therefore, the agreement obliges the States to guarantee collaboration with any natural or legal person, national or foreign, subject to national jurisdiction, interested in decision-making and monitoring of any development activities, public or private, with actual or potential environmental effects. It also obliges the States to guarantee these persons access to justice to resolve discrepancies in any type of development that presumably affects the environment.

However, once the national instances of justice have been exhausted, it allows appeal to international jurisdiction, opening the door to the final and binding ruling of entities such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR Court) and the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Francisco Tudela, jurisconsult, Harvard University professor and former Peruvian Foreign Minister states that “once the national instances have been exhausted, the final destination of any controversy on environmental impact within the framework of the Escazú Agreement is the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, whose rulings would be legally binding”. Therefore, those who would finally decide on any activity related to land management, whether public or private, would not be the national courts, but the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

Voices against the agreement

Because of this, regional actors such as engineer Centeno, jurist Tudela or community organizations such as the Peruvian Amazonian Commonwealth, which brings together regional governments, consider that the agreement is a legal mechanism for transnational powers to interfere and decision-making power with respect to the resources of the countries of the region.

It is “clear that decisions about our environment and its controversies will be transnationalized. They will no longer depend on Peruvians or our public institutions, but on international organizations, located outside our borders and committed to interests foreign to national ones”, indicated the members of the Peruvian Commonwealth.

The agreement allows environmental defenders to take measures to defend their rights and environmental “health”. In this way, international organizations will be able to restrict and control the self-determination of Latin American and Caribbean states with respect to the management of their natural resources and territories. Basically, “all decisions on development activities, use of natural resources and territorial management will be subject to the will of third parties, instruments not elected by the will of the citizens of each country,” said Centeno.

The third parties referred to by Centeno are mainly NGOs and national or foreign foundations with authorized residences in the country, most of which respond to interests alien to those of the nation where they operate. In fact, many of these entities use their power to influence local activists and organizations.

In addition, many of the local NGOs and foundations are often financed by international organizations to which they should respond, such as transnational environmental organizations, organizations like USAID, international cooperation agencies of developed countries, among which the Spanish AECID stands out, or private organizations such as the Gates, Ford or Open Society Foundations, to name but a few.

For all these reasons, for Centeno, “the Escazú Agreement is a legal barbarity that is only being tried out in Latin America as a perverse modern colonization mechanism, coupled with other initiatives for the control of the immense resources of this privileged region”.

*Translated from Spanish by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva