What is legitimate and what is not? Should governments negotiate with terrorist and criminal networks to reduce crime and homicide? Both questions, and many others, arise under this theme. In terms of security and negotiations, there is a wide constellation of cases between states, insurgent groups, and guerrillas, but less so with terrorists or drug cartels.

Since the international crusade against global terrorism began in September 2001, the adage among governments has been that terrorism is not negotiable. The argument, a little rusty and anachronistic, responds to a logic of legitimacy and of not letting state institutions be seen as weak units within democracies. A rather reductionist vision that minimizes even the role of the State in social relations.

Thus, the only viable and apparently legitimate recipe was centered on generating formulas for intelligence, military operations, strategic alliances of multilateral coalitions and police actions that would anticipate or neutralize terrorist and criminal networks. Formulas that targeted only the consequences of terrorism and not its roots. Well, to avoid the explosion of a bomb in a subway car or in an airport, it is as easy as to try to cure cancer with a painkiller.

In fact, as the IRA stated in 1984, after the attack on the Grand Hotel in Brighton, while terrorists need to get lucky once, states need to get lucky always. Contemporary unconventional security problems are a race to reduce the margins of error and prevent the time factor from being the main enemy of the opposing sides.

Against all odds, Donald Trump built a negotiating bridge with the Taliban in February 2020. The agreement was guided by incentives, the center of gravity of all negotiations. As agreed, the Taliban pledged not to allow Al Qaeda, ISIS or any other extremist group to operate within their areas of control. In return, NATO and Washington withdraw their presence from those sites.

The equation is based on the notion of victory and this, no longer translated into conquered territories or the number of casualties of the adversary, is determined by the construction of legitimacy

This is a basic and mature equation of conflict in which the parties know that mutual deadlock is the unfeasibility of success for either party and the deterioration of their objectives. The equation is based on the notion of victory and this, no longer translated into conquered territories or the number of casualties of the adversary, is determined by the construction of legitimacy in geographical spaces, of governance and capacity of agency in the face of social problems. Situations that, despite their barbaric nature, the terrorist groups in the area were beginning to build in the Afghan population.

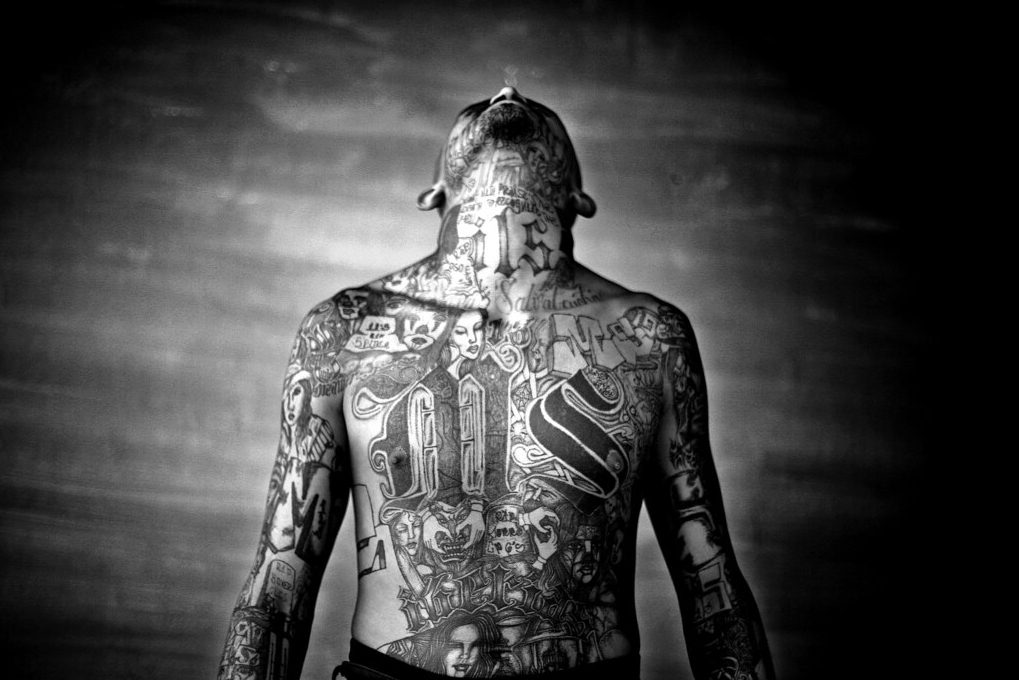

In El Salvador, Nayib Bukele has been weaving negotiating scenarios from prison with the world’s most dangerous gangs for about a year. With his plan he managed to reduce the homicides drastically after the post-conflict resulting from 30 years of civil war. But why negotiate with terrorists and criminals? It is, without a doubt, a complex question, but with ample strategic reasons.

While classic insurgencies have on their radar screen replacing the state, take power and manage the establishment in their own way, criminal and terrorist groups often aim to control “underground” resources, territorial disputes with the state and illegal economies. Ultimately, these groups have, on the one hand, the idea of being invisible in the eyes of the State and, on the other hand, use violence as a method to achieve a political end.

Thus, in the face of the above question, negotiation with these actors can be highly costly if the organization is not dismantled and its operations reduced in a short time. The answer is that negotiation is a window of opportunity since irregular actors have built parallel orders and criminal governance in the territories they operate in.

It has been demonstrated that with exclusive military and police methods, drug trafficking is not eliminated

It has been demonstrated that with exclusive military and police methods, drug trafficking is not eliminated, terrorism persists, and criminal groups become increasingly wealthy and act as subaltern states. Therefore, the equation to mitigate these scourges relies on two elements. On the one hand, the methodology and on the other, the incentives. The method requires, in principle, the following steps: first, the mediation of the State to bring about a ceasefire between gangs, armed groups, and terrorists; and second, a transformation of legitimacy, in which the State must build a counter-legitimacy over the illegal groups.

The incentives lie in calculating that negotiations can only be effective if the process focuses on the interests of the parties, not on the effects of their criminal or terrorist activities. In societies where violence and crime are generated by gangs, mafias, and groups of different natures, criminal networks are often so entrenched that negotiation may, in fact, offer the only viable solution. Therefore, the moment when the codes and patterns of the gears of crime and terrorism are deciphered, the State can propose a sustainable negotiation. Negotiating with terrorists and criminals can be the future of anti-terrorism and criminal policy.

*Translation from Spanish by Emmanuel Guerisoli

Photo by markarinafotos at Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND