A popular idea in economics holds that poor countries tend to grow faster than rich countries. Therefore, the economies of the world eventually converge in their income levels. The most important advantage that laggards have is to copy the best institutional, technological, and productive patterns and practices of those ahead.

Moreover, according to the theory, the poor receive large amounts of capital from the rich, which means that although they invest more and more capital in training their labor force or in their industries, the returns they get from these investments are diminishing.

What does the theory look like in the light of history?

After the English Industrial Revolution and the modern economic growth it spawned in the mid-18th century, a dozen Western countries reached income levels similar to England’s in the next hundred years. First came Holland and Belgium. Then France, Switzerland, Denmark, Germany, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and Argentina. At the beginning of the last century, the group of the rich was completed by Norway and Sweden.

The United States deserves special mention, as it overtook England to become the richest country in the world, the technological leader, and the hegemonic global political power on the brink of World War I.

Since then, there has been little convergence. During the so-called “golden years” of the postwar period, the rapid economic growth experienced by Austria, Finland, Italy, and Spain brought them into the elite club. Ireland and Portugal have recently joined.

What about Latin America?

The region has not been completely immune to the phenomenon. However, historical experiences of convergence have been bitter.

Argentina was one of the 12 most prosperous economies in the world during the first third of the 20th century and since then began a long gradual (relative) decline in its GDP per capita until the 2000s. It was overtaken by Venezuela in the 1950s, whose economy grew rapidly for another two decades, only to suffer a major downturn and another 30 years of stagnation. Thus, Venezuela shows an evolution of its income close to the shape of a bell of normal distribution. Evidently, in neither case was convergence cemented.

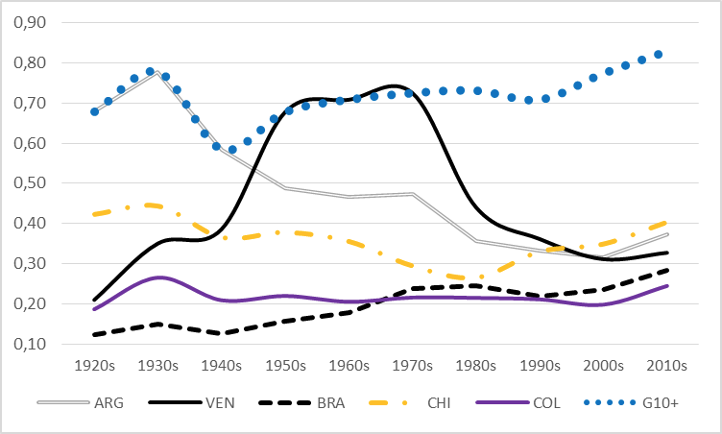

Figure 1. a century of convergence (or divergence) in Latin America, 1920s – 2010s (Evolution of real GDP p/c, 2011 US$ – Ratios of selected countries to the United States)

Source: Own elaboration based on the Maddison Project Database (2020). G10+ (average of the group of rich countries mentioned above, of which Argentina and Venezuela were temporarily part in different decades).

Although the cases of Chile and Colombia are similar, in that both end their trajectories at income levels very close to their starting points a century ago, Chile lags markedly behind the G10+ for 50 years (1930 to 1970), and only begins to recover in the 1980s. Colombia, meanwhile, has remained virtually static since the 1940s, with a turnaround in the last decade.

Brazil looks different. It shows an upward trend only slowed by the debt crisis of the 1980s and the subsequent “lost decade”. In 100 years, Brazilians’ income has gone from just over 10% of US income to 28%. At this rate, convergence with the leader will take about 300 years.

The success of Asian countries

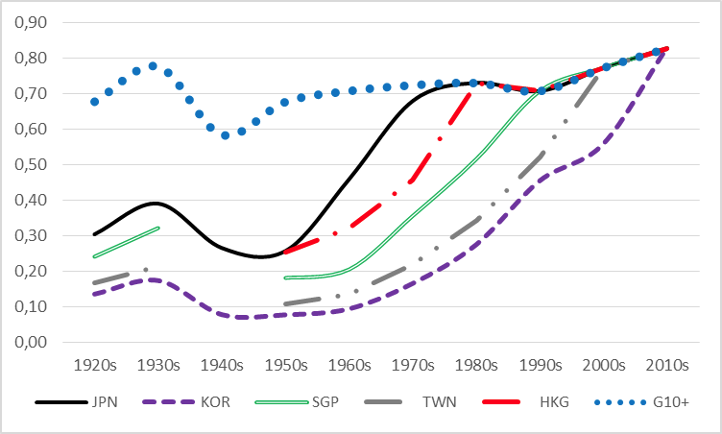

Latin America’s failure to converge is clear and convincing. But not all have suffered this fate. The experiences of Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea (the Asian “tigers”) represent successful cases of convergence.

Starting with Japan in the 1960s, and successively with differences of about a decade between the 1970s and 2000s, the remaining four cases in the above order have reached the income levels of the G10+. While they did so at different growth rates, Hong Kong and Japan at very high rates and Korea at a slower pace, they all reached the promised land.

Figure 2. A century of convergence in East Asia, años 1920 – años 2010

(Real GDP growth p/c, 2011 US$ – Ratios of selected countries to the United States)

Source: See note Figure 1. In different decades the Asian “tigers” have become part of the G10+.

What is the difference?

The decisive factor in understanding the reason for the dissimilar experiences in the two regions lies in the nature of integration with the international economy.

On the one hand, Latin America was integrated through primary exports. Throughout the century, the export matrices of the five economies were dominated by commodities: coffee, wheat, meat, rubber, wool, soybeans, copper, nitrate, coal and oil.

On the other hand, the “tigers” gradually transformed their matrices, moving away from the export of primary goods to concentrate on the development of industrial goods exports (and commercial and financial services in Singapore and Hong Kong). The years of rapid growth and convergence were years of dynamism and consolidation in sectors such as automotive, high-precision machinery, synthetic fibers, plastics, semiconductors, computer software and electronic products. All of these competed in international markets. In other words, these economies gave a big boost to their industrialization by redirecting it towards exports.

Export industrialization stimulated demand for domestic activities linked to production abroad, generating increasingly better qualified formal jobs, and allowed the accumulation of savings to be rechanneled as investment in infrastructure and other resource-hungry sectors.

But, above all, this export commitment required the formation of a national technology system capable of continuous innovation, both in products and production processes. Thus, Asian firms and workers became more productive and added ever greater value to the goods and services offered. As a result, they received higher incomes.

To be fair, Latin Americans did manage to export industrial goods. But they did so in smaller proportions, mostly at the regional level, and episodically. Technology was imported instead of being created at home and the virtuous circle was disrupted.

Commodities took a different path, with long-standing structural problems: external vulnerability, currency devaluation, growth volatility and scarcity of stimuli and links with other activities.

The world has changed, and the news is not good. The conditions for leaping ahead are more difficult now than they were for the “tigers” four or five decades ago. Bilateral trade agreements, the rules of the international trade regulatory game, and the ubiquity of intellectual property rights have significantly reduced the space for developing the kind of industrial policies that the now rich implemented when they sought to emerge from poverty.

Latin America seems doomed to contribute to theories of divergence.

Translation from Spanish by Destiny Harrison-Griffin

Photo by cliff.hellis at Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND