In Colombia, the transformation of the so-called ollas (hubs) of micro-trafficking—open-air drug-selling places where illicit drugs are sold and consumed constantly—reflects a structural phenomenon that is surpassing the realm of ordinary crime. Far from being limited to improvised points of sale, these criminal nodes have evolved into forms of convergent criminality that are highly functional and adaptive.

In cities such as Bogotá, where more than 350 active points controlled by at least 79 specialized criminal structures have been identified, the ollas operate as logistical platforms that link narcotics distribution with dynamics of territorial control, money laundering, the instrumentalization of minors, and the co-optation of public services, thereby expanding their operational capacity and their resistance to state intervention.

This is not simply a local expression of an urban security problem. The ollas constitute a criminal subsystem with multiple interdependencies that cut across territorial, social, and geopolitical dimensions. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) warns that there is evidence that urban environments dominated by micro-trafficking function as spaces for the recruitment and exploitation of vulnerable populations, especially irregular migrants, bazuco users, homeless people, and sex workers.

Therefore, from a strategic intelligence perspective, they must be understood as lower-level links within a criminal architecture that connects diverse illegal markets, including arms trafficking, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking for the purpose of organ extraction.

A deeper problem

The persistence of the ollas lies in their ability to anchor themselves in contexts of marginalization, inequality, and institutional weakness. The ollas tend to be deliberately located in environments of high institutional and social vulnerability, especially around school zones, tourist corridors, or areas of urban convergence. This choice is not accidental: it responds to a logic of expanding the consumer market and early recruitment, which turns students, youth, and visitors into potential targets for criminal capture.

At the same time, proximity to schools facilitates early initiation into the consumption of psychoactive substances, while operating in tourist zones enables the movement of drugs and their commercialization in circuits that are difficult to trace, deepening local insecurity and exacerbating the fragmentation of state control.

As a corollary, these enclaves of illegality produce a phenomenon of criminal irradiation, widely documented as “criminal contagion.” It involves the spread of associated crimes—robberies, homicides, and extortion—into the surrounding environment, increasing levels of violence in neighboring areas. But these are not merely collateral effects: at its core, this is a direct manifestation of the power exercised by criminal networks over urban space. In this context, violence operates as a tool of territorial discipline and community deterrence, consolidating an architecture of fear whose effect is the weakening of institutional presence.

The phenomenon has also given rise to the diversification of distribution methods, which are no longer limited to traditional fixed selling points. The logistical sophistication of the trade includes mobile forms such as the mano blanca model—in which drugs are deposited at georeferenced points for anonymous pickup—scheduled deliveries through messenger services, or mobile vending. Indeed, from within the ollas, strategies of evasion and territorial fragmentation typical of transnational organized crime are now being emulated.

The operational resilience of the ollas is largely explained by their anchoring in a highly profitable illicit economy capable of sustaining daily revenues amounting to tens of millions of pesos, even under sustained institutional pressure. Their financial capacity fuels continuous processes of criminal professionalization, materialized in increasingly dynamic, decentralized, and flexible logistical structures. Tactical use of the urban environment has enabled them to adapt quickly to enforcement operations, shifting their activities without interrupting the flow of illicit trade.

The result of this structural transformation—beyond logistical challenges—aligns with the rise in national drug-consumption patterns. According to UNODC data, in 2023 Colombia experienced a 53% increase in the production of pure cocaine, reaching 2,600 tons, of which approximately 20% was destined for the domestic market—a market generally supplied by the ollas.

In this context, the sustained expansion of local consumption cannot be understood in isolation but rather as the direct result of the territorial and functional consolidation of the ollas as highly efficient criminal infrastructures, rather than mere points of sale.

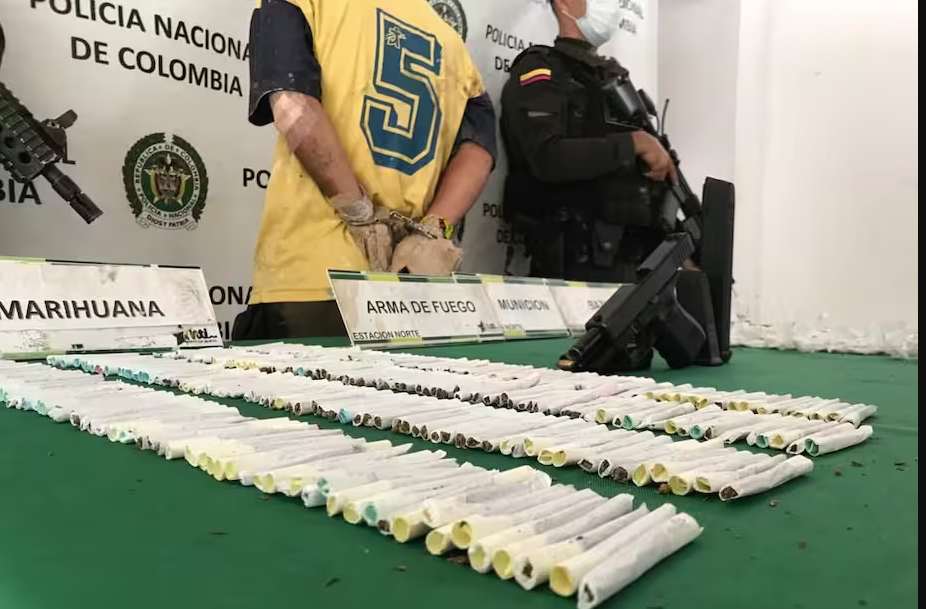

The arrest of the minor under 14 years old as the alleged perpetrator of the attack against Miguel Uribe Turbay once again exposed the ways in which micro-trafficking networks instrumentalize youth in vulnerable urban contexts from within the ollas. According to the Prosecutor’s Office, the teenager had been hired by the leader of an olla in the Villas de Alcalá neighborhood, where operations are underway to locate the mastermind behind the attack.

How to respond?

The state’s response to this phenomenon has been primarily punitive, focused on interdiction operations and the dismantling of gangs, such as the intervention that identified and disrupted 60 ollas in the first months of 2024 in Bogotá. However, these efforts—while necessary—are insufficient and often ineffective when not accompanied by comprehensive policies aimed at harm reduction, prevention of drug use, and the socioeconomic reintegration of affected populations.

Examples such as the experience of the La Favorita neighborhood in Bogotá, where an olla was replaced with an urban garden and social-inclusion programs, demonstrate that it is possible to transform territories under criminal control through sustained strategies of urban development, community participation, and institutional coordination.

Despite experiences like this, such initiatives remain scarce and marginal compared to the scale of the problem. The lack of coordination among the judicial, health, and social dimensions of the phenomenon prevents addressing its root causes, perpetuating a reactive model focused on repression rather than on transforming the structural conditions that sustain micro-trafficking.

This approach is key not only to preventing illegal markets from diversifying and decentralizing but also to mitigating the risk that the ollas become strategic platforms within a transnational system of illegal economies.

Understanding the problem as a hybrid logic—local and global, informal and structured—requires rethinking the normative and institutional framework with which the Colombian state approaches urban security, since the partial understanding of the phenomenon, centered on its most visible criminal expression, has constrained the formulation of multidimensional responses, generating fragmented and short-term interventions.

From a public-policy perspective, the challenge is to abandon the mono-causal view of micro-trafficking as a policing issue and move toward a complex reading that situates it at the intersection of three key dimensions: security, public health, and social development. This entails, first, strengthening criminal-intelligence capabilities to map complex networks of urban criminality, including the detection of financial and logistical patterns linking ollas to money laundering and other illicit activities. Second, a national harm-reduction strategy is needed, including mental-health care, addiction treatment, community education, and economic alternatives for at-risk youth. Finally, a security-oriented urbanism is required to reclaim public space through social infrastructure, citizen participation, and effective institutional control.

Ultimately, the response model must be inter-institutional and evidence-based, avoiding symbolic solutions that, while media-friendly, prove ineffective against criminal resilience.