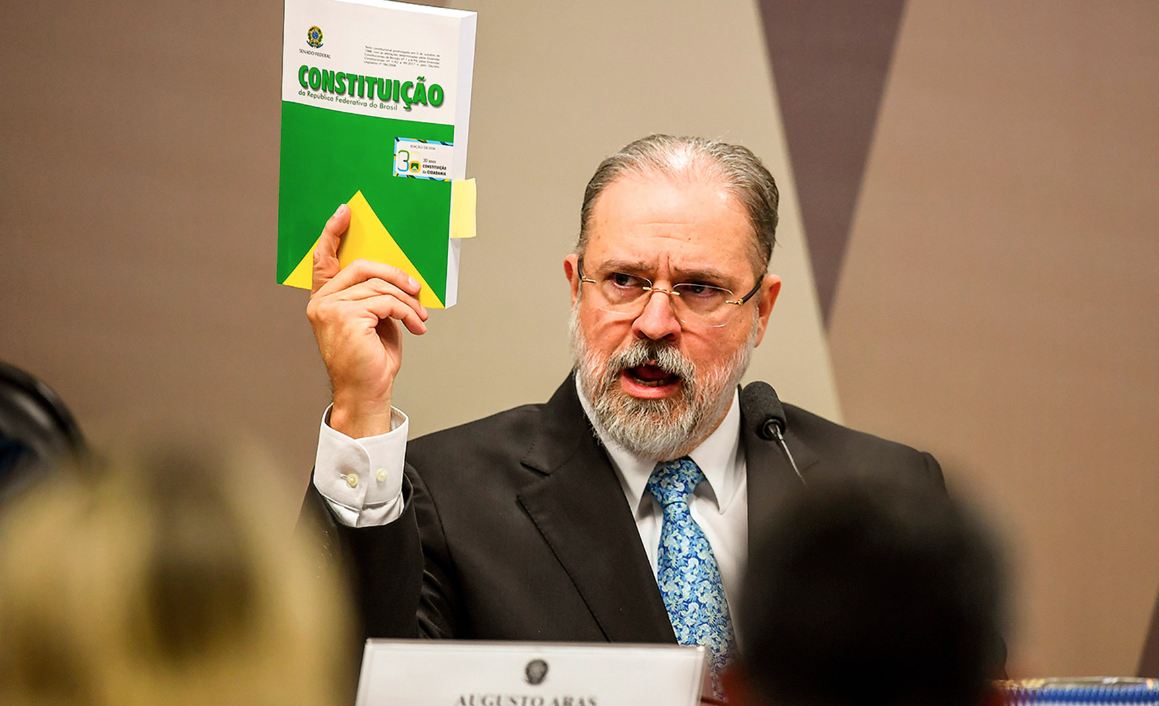

There is consensus among Brazilian political analysts that Augusto Aras, the current prosecutor general, has had a disastrous performance, to say the least. Instead of combating the excesses of Jair Bolsonaro and his entourage, the head of the Prosecutor’s Office has been an accomplice of the former president. Although the diagnosis is correct, the explanation of why Aras behaved this way is often wrong.

Attributing to Aras an ideological alignment with Bolsonarism, or even a kind of deviation of character is inaccurate and difficult to prove. In addition, cannot explain the apparent change of position that the prosecutor general adopted after the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2022. The key to understanding the behavior of the prosecutor general lies in the manner of appointment and especially in the possibility of a 2-year term renewal, not only of Aras but of the others who have already passed through this position. He is, above all, a careerist, but not necessarily a man of the far right.

Augusto Aras, like his predecessors, followed the rules of the game. Rachel Dodge, appointed by Michel Temer in 2019, authorized only cases against Bolsonaro when she no longer had a chance of being reappointed as head of the Prosecutor’s Office by the new president, according to the press. Rodrigo Janot, for his part, worked during his two terms in office in favor of the interests of his colleagues in the Prosecutor’s Office, when they would be the ones to choose the chief of the institution (Lula and Dilma Rousseff almost automatically accepted the appointment of the one most voted by the members of the institution themselves). Geraldo Brindeiro, who was appointed and re-elected thrice by Fernando Henrique Cardoso, became known as the “republic’s archivist general” for filing many accusations against the government.

With an eye on his candidacy in 2018, Aras did not participate in the election organized by the federal prosecutors because he knew that Bolsonaro would not listen to the corporation’s wishes. In seeking re-election in 2021, he was able to show that he was prudent with the then president, even being considered by Bolsonaro himself for a future vacancy in the Supreme Federal Court (STF).

Aras hardly bothered Bolsonaro until the results of the polls were known in 2022, still hoping that the pen of the then-president could take him to the STF or another term as chief prosecutor. Now, with a new president and no chance of retaining important positions, he is trying to clean up his worn biography a bit by acting against the terrorists who attacked Brazilian democracy this year. Shame is what remains of Aras’ reputation.

The current prosecutor general defends himself by saying that it is not true that he had protected former president Bolsonaro. He recalls that he acted in some cases, but that he avoided the politicization of the times of Operation Lava Jato. The partial numbers of his performance, however, do not seem to support this position. The chief prosecutor filed several allegations that the president had acted criminally in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, which were presented by the Senate’s Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI).

During the 2022 election campaign, the most violent since re-democratization in 1985 and which was marked by the use of fake news by Bolsonaro’s allies, Aras, who is also the electoral prosecutor general, did not employ electoral justice on any occasion regarding the use of lies and fake news, according to a report by Folha. An investigation by Transparency International indicates that he has opened fewer corruption-related Criminal Investigation Proceedings (PICs) than his predecessors.

In 2016, still with Rodrigo Janot as prosecutor general, there were 577 PICs. Under Aras, these numbers were reduced to 366 in 2019, 200 in 2020, and 241 in 2021. The STF and its ministers had to adopt heterodox measures to circumvent the inertia of who holds the monopoly of criminal prosecution in relation to the president, ministers, and parliamentarians.

Aras’ mandate ends in September. Lula did not commit himself to respect the election organized by the federal prosecutors (and rightly so). The experience of a prosecutor general having his own colleagues as voters also proved disastrous. Janot, who headed the Prosecutor’s Office during Operation Lava Jato, did as much damage to Brazilian democracy as Aras.

And the issue is not necessarily the political position of both. The problem is that the possibility of being reappointed in office or occupying other prominent positions in the Brazilian state, such as the STF minister, incites the chief prosecutor to act in a way that can be considered improper.

When a president appoints and renews the mandate of the prosecutor general without consulting the members of the Prosecutor’s Office, as Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Bolsonaro did, we witness the occupants of the top position of this institution excessively lenient with the heads of the Executive.

When, on the other hand, the power of appointment is transferred to the 1,200 public prosecutors, as Lula and Rousseff did, we run the risk of having an occupant of a powerful office with no political limit other than his own corporation.

It is necessary to end the possibility of renomination and the creation of a long quarantine for those who occupy the position of the chief prosecutor. Otherwise, Brazil will always return to the same dilemma from time to time: excessive independence or lack of autonomy, two extremes disastrous to democracy.

*Translated from Portuguese by Janaína Ruviaro da Silva