One of the backbones of democracy is conflict. The human being is conflictive by nature, not violent, and democracy, through political parties, institutions and a whole regulatory cast of freedoms, guarantees, rights and duties, channels conflicts and resolves them in an institutionalized manner. However, in Colombia this does not happen.

There, social protest, which is a right inseparable from democracy, thanks to which the needs or disconformities of citizens are problematized, made visible and politicized, tends to be criminalized. That is, resolved from a relationship as asymmetrical as it is annoying, in which political elites and the repressive apparatuses of the State reduce protest as a mere antithesis of the social order and, therefore, the more society is silenced, the better.

any hint of social change, of expression of unrest, of denouncing the abuses of the State, was susceptible to being sympathetic to the guerrillas

The internal armed conflict has not helped either. Its scope and meaning allowed for the constitution of a reality of black and white, without nuances, where any hint of social change, of expression of unrest, of denouncing the abuses of the State, was susceptible to being sympathetic to the guerrillas and, by extension, to violence. Expressions such as “to form a union” or “mamerto”, which in other countries like Peru has its equivalent in the word “terruco”, only stigmatize protest and criminalize it.

Unfortunately, social mobilization has to be given substance in totally different terms in Colombia. On the one hand, it did not play in their favor that for decades, and asserting the thesis of the French sociologist Daniel Pécaut, the social transformation of the State was patrimonialized by the guerrillas. Expressed in another way, it is as if the needs and demands of society had been reduced for decades to the state-guerrilla binomial when, in reality, this was never the case.

On the other hand, the political elites, generally, have been accustomed to deactivating social mobilization without dialogue and mostly concessions. That is, either by means of repression, or by co-opting certain social sectors in exchange for deactivating the demand and confrontation. However, in a transformation of the paradigm of social mobilization, these responses seem to be of another time and moment and, therefore, they have more and more difficult to grasp in these times.

The Colombian public forces, like their leaders, have not yet learned that the course of social protest is resolved democratically

The Colombian public forces, like their leaders, have not yet learned that the course of social protest is resolved democratically through cooperative exchanges and that they must learn to de-Securitize it. Protest is neither a threat to the interest of the state, nor does its social and political expression call into question the foundations of the system in terms of rupture.

For decades, the influence of the National Security Doctrine allowed a necessary militarization of security in the country, which could be extended to the whole continent, reduced to repression and persecution of any demand for change. With the end of the Cold War and the disappearance of most of the insurgencies and guerrilla movements, the persistence of the armed conflict in Colombia made the change of paradigm unnecessary.

That is, security and defense have different paths, different functions and vocations, and totally different relationships with the citizenry. But in the end, the armed conflict favored the continuity of simplisms in which society, when it organizes itself and acts showing its discontent, as long as it alters the status quo, ends up being reduced to a mere enemy on which the State must deploy all its strength.

The police forces of democratic systems have long understood that their relationship with the citizenry and their multiple expressions of protest must be normalized and institutionalized, so that the evocation of repression must be strictly marginal and exceptional. The opposite is true in Colombia, where the army and the police often overlap and where excesses against the citizenry have become too many “bad apples” to justify.

As much as it may cost some political leaders, and also certain commands of the Public Force, as far as the Police is concerned, they must assume a necessary transformation in their role and in their understanding of security. Thus, it is time to move from national security, and even public security, to a citizen security of greater proximity, closeness and attachment to society and the local context.

Otherwise, a legal framework and orientation that is more appropriate to another time and, above all, another place, will continue to be nurtured. I insist, also a measure of the quality of democracy is the role that the police assume in the system, of how they interact with society, and of how they render accounts, in a transparent manner, to each other.

To demilitarize the police is not only to remove them from the military, it is to train them in human rights, tolerance and democratic coexistence. It is to guarantee rigorous processes of selection, promotion and recognition. But it is also to achieve effective mechanisms of sanction and transparency to ensure that the missionary concept and values of the high and medium commands of the institution permeate the whole body.

This is perhaps one of the most complex issues that Colombia must address. That, and that the civil power, to which all police apparatus is subsumed, can demand and condemn abuses and outrages that, in all evidence, are undesirable. It cannot be that the response of the Government of Iván Duque to events such as those of last week invite to think that it is the citizenship, in its attitude of protest and disenchantment, the responsible for the misfortunes that ultimately have happened.

*Translation from Spanish by Emmanuel Guerisoli

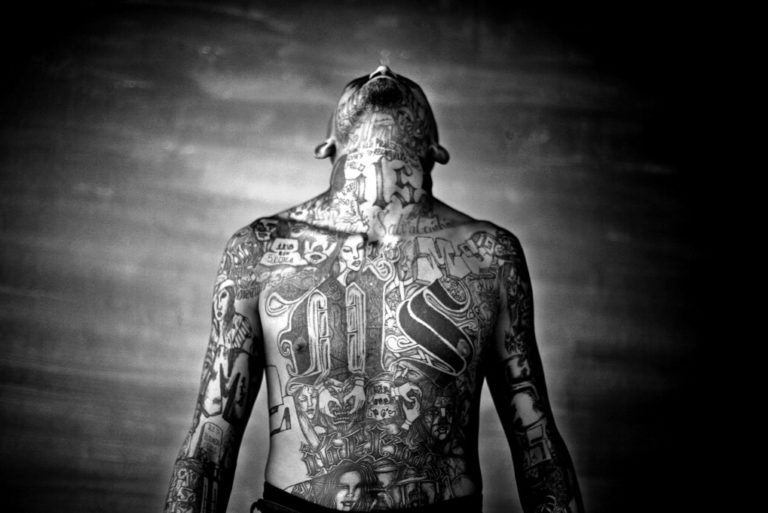

Photo by Oneris Rico at Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA