The COVID-19 pandemic abides. Growth in the number of infections and the number of positive people in Europe and America indicate that the disease is re-emerging in these areas. In some countries the spread of the disease hasn’t been significantly controlled and, in recent weeks, there has been a further escalation in the numbers. The United States stands out, in the midst of its long electoral process, with contagion figures nearly exceeding one hundred thousand people per day, indicating that in the coming weeks, pressure on its health system could be significant.

Health care systems have been stretched to the limit, with insufficient investment in expanding and modernizing their infrastructure, let alone insufficient recruitment of qualified health care professionals over the course of the pandemic. In Europe, street demonstrations by various citizens groups over new confinement measures are noteworthy. In Germany, as in Spain and England, there are expressions of this nature that, by themselves, do not help to curb COVID-19 contagions. In several countries in America there are also protests, and yet they are motivated by other purposes. The common sign in the region is to protest against the results of the economic and social management conducted by the authorities for many years

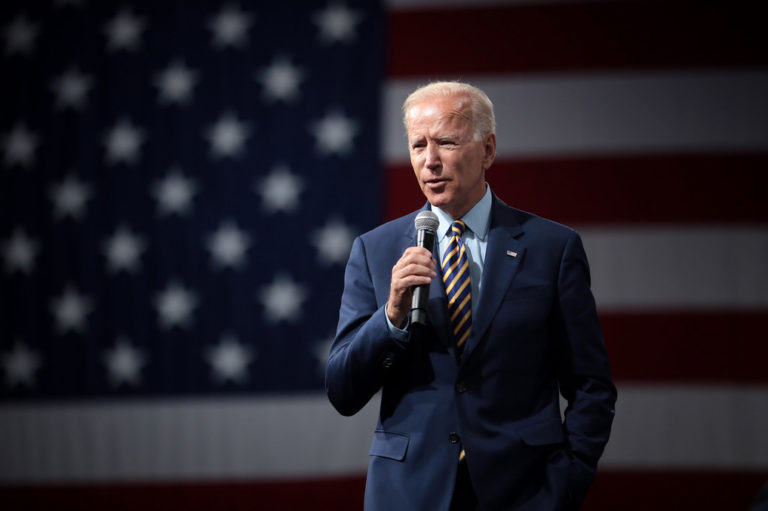

In the United States there is a broad social movement against racism, police brutality, and violence against women. In recent weeks, it has been linked to the presidential elections, House of Representatives, part of the Senate and some governorships. This is an issue that requires specific analysis. For the time being, consider the remarkable extent of the social movement against inequality. This in a context where the proposals of the Republican Party, led by Donald Trump, have the electoral support of more than 70 million citizens — 47.7% of those who exercised their vote. In the meantime, the management of the pandemic and economic-policy measures will advance with difficulty amid this context.

In Latin America, in the political scenario, the social movements and political parties located in the space of the struggle against social inequality

In Latin America, in the political scenario, the social movements and political parties located in the space of the struggle against social inequality and the political expressions that make it possible stand out. In Chile a broad movement of citizens managed to win the plebiscite to legislate a new Constitution that will be the subject of deliberation in a constitutional convention starting in April 2021.

Popular action must continue. Precisely, the continuity in popular action and the capacity to achieve common goals is a relevant fact of the recent triumph of the MAS in Bolivia. It will still be necessary to complete the restoration of legality with the inauguration of President Arce and then, as the president-elect recognizes, to carry out the most important tasks in the area of redirecting the economy and politics in order to make progress in reducing social inequality and creating conditions for a dignified life for the majority of the population.

This is the point at which other countries, such as Mexico and Argentina, find themselves with governments that declare their distance from neoliberal positions and must advance in a notable economic and social reconstruction that will be the seat of new political relations in each country. The pandemic further complicates the scenario, but in a sense it forces more far-reaching decisions in the reorganization of the economies.

In other countries in the region, social movements are continuing, with their specific forms of development as in Colombia, adding the demands of the original inhabitants, women, urban dwellers and the full implementation of the peace agreements. In Ecuador, in a few months, presidential and legislative elections will be held, which could be the space for the multiple partisan and social movement built against the program of restoration of the structural reforms of the current government to achieve an electoral victory. The social mobilization is taking place in the difficult context of the continuity of the COVID-19.

the multilateral financial organizations are considering the emergency situation, but they are not proposing measures that effectively overflow the space of structural reforms.

All of this is happening while the multilateral financial organizations are considering the emergency situation, but they are not proposing measures that effectively overflow the space of structural reforms. The thesis of the external shock is maintained and that once the pandemic is overcome, it will be possible to return to normal economic behavior.

There is no recognition of the long period of weak growth in the economies of Europe and America and the advance of social inequality. In October, within the framework of the meeting of the IMF and the World Bank, the 42nd session of the International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC) was held, composed of the finance ministers or the presidents of the central banks of the largest developed economies and other guests, which recognized the difficult situation resulting from the pandemic.

But it also notes that, going forward, once the health crisis is behind us, action will be taken based on what the IMFC defines as its pre-health crisis agenda. This means moving forward with structural reforms.

For the time being, the functioning of the international monetary system is placed in first place, which includes the provision of substantial resources by central banks that allow for the benefits of a small group of participants in these markets, without improvements in the rest of the economic activities. For most of the population there is no improvement in their living conditions. In Latin America it means the maintenance or increase of social inequality.

*Translation from Spanish by Ricardo Aceves

Foto de Eneas en Foter.com / CC BY